Georges Seurat’s most famous painting, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884), hangs at the Art Institute of Chicago, where visitors jostle forward and back to observe the composition as a whole before moving in to the study the technique—pointillism—that’s made this work an art historical icon.

It’s well known that Seurat used dabs of separate hues that coalesced to create images when viewed from afar while dematerializing into abstract patterns upon close inspection. But the crowd around La Grande Jatte may also become aware that they’re being mirrored by those within it, a cross section of Parisians enjoying the views on the island in the Seine from which the painting takes its name. Other museumgoers may register the contrast between their own constantly shifting selves and the scene’s nearly total absence of movement, a preternatural stillness designed to recall the decorated walls of temples and tombs. “I want to make modern people, in their essential traits, move about as they do on those friezes,” Seurat once wrote, “and place them on canvases organized by harmonies of color.” Yet Seurat’s stated wish to fix transient moments for eternity obscures the radical nature of both the painting and Seurat’s art in general.

Seurat was hardly alone in painting contemporary life during la belle epoque, as the examples of Manet, Renoir, and Caillebotte attest. But while the Impressionists tended to gravitate toward the “new” Paris of boulevards plowed through its old medieval clutter, Seurat often used the city’s industrialized suburbs as a backdrop. He leveraged the era’s studies on optics to suffuse his subjects within clouds of dots lofted by the larger social and technological transformations of the late 19th century (echoing, for example, the color-separation process of chromolithography, the most advanced form of commercial printing in his day). And he atomized the continuity of the picture plane, a move exceeding anything his coevals attempted.

-

Early life and career (1859–1883)

Image Credit: Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Born 1859 in Paris, Seurat had his life cut short at age 31, though the cause of his death has been debated. (Some say diphtheria; others, pneumonia.) His father, a former bailiff, made his money in real estate and lived separately from his family though he visited them weekly. Seurat often went to his father’s house to paint in its garden.

Seurat began to draw in his teens and entered the École des Beaux-Arts in 1878 under the tutelage of the painter Henri Lehmann, a disciple of Ingres. Ingres’s crystalline if languid neoclassicism was evident in the young Seurat’s figure studies and remained an influence throughout his career.

Seurat interrupted his education for a year of military service in Brittany, after which he returned to Paris to resume his studies. He shared a studio with his friend the painter Edmond Aman-Jean, and both expressed an admiration for the landscapes of Jean-François Millet, the Barbizon School founder known for limning bucolic settings populated with stolid peasants. The two made frequent excursions to La Grande Jatte, and Aman-Jean would become the subject of a charcoal portrait Seurat successfully submitted to the 1883 Salon when he was just 23, one of countless such drawings whose ephemerality make them appear rendered with smoke.

By then, Seurat had already begun reading treatises on color theory and perception. He was especially taken by The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors, written in 1839 by the noted French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. Indeed, empirical literature became the foundation of Seurat’s work. “Some say they see poetry in my paintings,” he once remarked. “I see only science.” Pointillism, which became a subset of Post-Impressionism, developed out of this thinking, though Seurat himself preferred the terms divisionism and peinture optique to describe a method that relied on the eye, rather than the brush, to mix colors within pictorial space.

-

Bathers at Asnières (1884)

Image Credit: Collection of the National Gallery, London. Still, pointillism didn’t factor into his first major composition, Bathers at Asnières (1884), though the painting laid the groundwork for his future approach. Presenting a group of men on the banks of the Seine, Bathers was rendered in brush marks that more or less blended together, often as choppy crosshatchings that foreshadowed Seurat’s signature facture. Seurat’s subjects are seen mostly in profile, with items of clothing (such as bowler hats) marking them as members of the proletariat. These signifiers are reinforced by the background placement of a factory sprouting chimneys that belch smoke. A bridge crossing the river in front of the plant is veiled with steam, suggesting the presence of a chugging locomotive, while the middle ground on the right includes the tiny figure of a man (whose bourgeois status is denoted by his top hat) and his female companion being rowed across the river in a boat. On the far right, a man in a racing skiff propels himself out of the frame. In essence, Bathers is a study on differences of class as seen through a lens of leisure pursuits made possible by modernity.

True to his predilection for friezelike arrangements of figures, Seurat endows his bathers with the solemnity of a Grecian entablature, importing as well the working-stiff pastoralism of Millet. Seurat also offers a sly nod to Ingres in the foregrounded mec wearing a white jacket as he lies on an embankment, his backside turned toward us in a pose as sinuous and inviting as that of an Ingres odalisque.

As was often the case with the French Academy, Bathers was spurned by the Salon of 1884 and was shown instead at the Groupe des Artistes Indépendants. Dissatisfied with the management of the show, however, Seurat became part of a breakaway group, the Société des Artistes Indépendants. Among its members were artists such as Henri-Edmond Cross and Paul Signac, both of whom would adopt pointillism. Bathers, then, became a catalyst for Post-Impressionism as a movement, though the painting that followed, La Grande Jatte, would become one of its most celebrated.

-

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884)

Image Credit: Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. La Grande Jatte represents the moment when Seurat’s engagement with Chevreul became concrete. He began work on it during the summer of 1884 and took two years to finish it. He completed some 70 preparatory studies for the piece, many of which were painted (mostly on board, with three done on canvas). In the painted studies in particular, one can see Pointillism evolving out of the crosshatching used for Bathers, for which La Grande Jatte serves as a companion piece, if not a mirror opposite.

The location of La Grande Jatte is just across the river from the spot on the Seine where Bathers is set, and just as in that painting, the subjects in La Grande Jatte are seen mostly from the side, though they face left, while the figures in Bathers look to the right. The same bridge from Bathers occupies part of La Grande Jatte’s background, while a racing scull similar to the one found in Bathers can be seen skimming across the water. Once again, Seurat used La Grande Jatte to meditate upon the leveling effects of downtime on social stratification.

As a formal matter, Bathers and La Grande Jatte offer a contrast in light and dark—while Bathers is awash in midmorning sun, La Grande unfolds under the shade of numerous trees studding the canvas—but does this text harbor a subtext? The answer is somewhat ambiguous, though the actual location of La Grande Jatte was a well-known pickup spot for sex workers, and there are hints of this within the painting. On the far left, a woman can be seen fishing, which has often been taken as a metaphor for solicitation. Then there is the strange detail of a monkey being held on a leash by a woman strolling arm-in-arm with a man—a symbol for her licentiousness, supposedly, because the French word for a female monkey, singesse, is slang for prostitute, though the gender of the animal is unclear.

Another debate around La Grande Jatte involves the little girl at its center staring out at the viewer—not necessarily to invite us in, but to question our own complicity in seeking out pleasure, for which the painting is practically a machine.

-

Pointillism in motion (1886–1888)

Image Credit: Collection of the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia. Photo: Tim Nighswander. Nonetheless, the extent of stylization within La Grande Jatte is such that even Seurat felt the need to walk it back a bit in his follow-up composition, Les Poseuses (The Models), painted between1886 and 1888. This depiction of Seurat’s studio is his most conceptual and reflexive effort, as it partially replicates La Grande Jatte behind a trio of nude models who are, in fact, the same woman in three different poses. Instead of rock-carved rigor, Seurat allows a supple naturalism to pervade the figures, who together evoke the three graces tradition of Old Master paintings. The nakedness of the models combined with the fully dressed cavalcade of people in the painting within the painting could also be read as a commentary on Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and its provocative juxtaposition of clothed and unclothed figures.

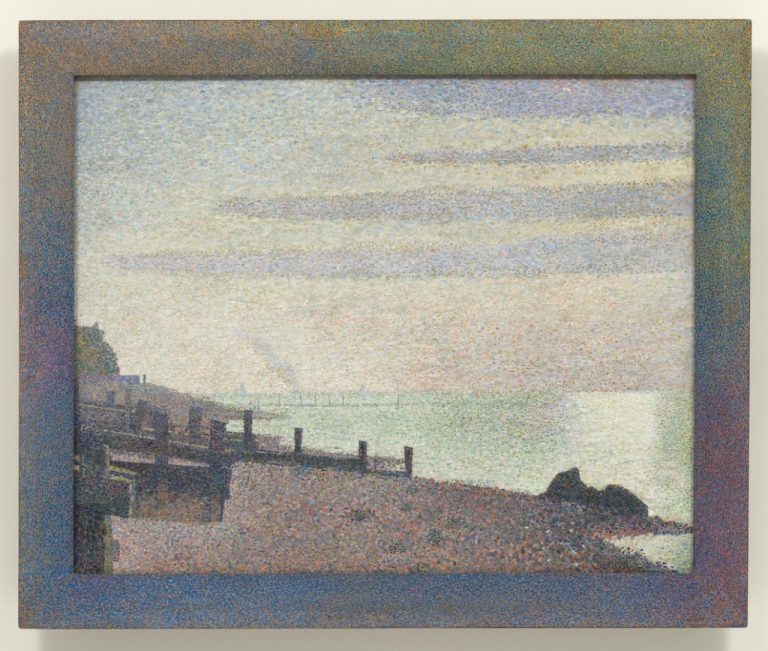

In the summer of 1886, Seurat traveled to the town of Honfleur on the Normandy coast, where he embarked on a series of views of its harbor. The most notable of these, perhaps, was Evening, Honfleur, which depicts a rugged stretch of beach at dusk. This austere seascape capped by a cloud-scudded sky possesses a quality of light made palpable as an aerosol of dots that a critic of the time compared to “gray dust.” Seurat’s pointillism spills over onto a purpose-built frame, replicating the setting sun’s shifting tonalities with a gradient of colors running from light at the top to dark at the bottom. Seurat had previously surrounded compositions like La Grande Jatte with bands of dots, but here they leap out of the picture to enter the realm of the viewer, a move that foreshadowed Minimalism’s emphasis on painting’s physicality as an object during the second half of the 20th century.

-

Final years (1888–1891)

Image Credit: Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In the last three years of his life, Seurat shifted in a couple of new directions, changing up the substance and style of his work. The first composition indicating as much was Circus Sideshow (1887–88), which, in a nighttime setting, introduced popular entertainment as a theme. The piece depicts the entrance to the Circus Corvi at Place de la Nation, a favorite attraction for the working class. A standing trombonist leads a band seated behind a balustrade that’s actually painted theatrical scenery. He plays to a crowd gathered in front, joined at the right by the circus ringmaster standing by a ticket booth. The whole scenario is illuminated by a fringe of gaslights at the top of the picture.

More so than even La Grande Jatte, Sideshow is gripped by immobility, limned in a kind of chthonic palette suggesting a subterranean flipside to the dazzling luminescence of Bathers. One can make too much of this as some sort of comment, but it’s likely that Seurat is simply differentiating the delights of artifice from those of nature.

Seurat’s final canvases are thematically related to Sideshow but diverge from it by a dramatic swerving into dynamism. Unlike just about every other Seurat painting, Le Chahut (1889–90) and Le Cirque (begun in 1890 but left unfinished) are all about motion. The first painting portrays a line of dancers performing the can-can at a nightclub; the second, various circus acts under the big top, including an acrobat, clowns, and most conspicuously a woman riding a galloping horse while standing on one foot. The action in Le Cirque is so frenzied that even the hair on the subjects’ heads take on a life of their own. As in La Grande Jatte and Evening, Honfleur, Seurat edges Le Chahut and Le Cirque with accretions of dots that extend beyond the image area, forming a proscenium arch in the former and migrating onto the frame in the latter.

-

Artistic Legacy

Image Credit: Collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Seurat’s pointillism continued to spread after his untimely demise, taken up directly by the aforementioned Cross and Signac, among others, while influencing the work of Fauvists such as André Derain and Henri Matisse. His deconstruction of painting would be furthered by 20th-century modernists, and a case could be made that the relationship between Seurat’s dots and the mechanisms of mass reproduction of his time reverberated through Andy Warhol’s and Roy Lichtenstein’s use of halftone patterns in the postwar era.

Ultimately Seurat’s work plumbed the way color reshapes perceptions of the world to provide a refuge from its harsher realities. “Let’s go and get drunk on light again,” he once said. “It has the power to console.”