Kim Hong-hee explains a vision of Korean art history in which no one is left out Korean Feminist Artists: Confrontation and Deconstruction (2024). Through essays on 42 artists, the curator and scholar traces the history and trajectory of Korean feminist artists from the 1970s to the present, focusing on 15 themes, including body art, queer politics, ecofeminism, and North American Diaspora—All but two of the artists are living. at the time of publication.

The publication is structured after Kim’s monthly column in Kim magazine Jingxiang News Published from 2021 to 2022, the newspaper will examine the work of Korean artists through a feminist lens in 17 issues. Phaidon’s book was originally published in Korean by Youlhwadang earlier this year and has now been translated into English. How do Western readers view this approach to Korean feminist art?

One consideration is the strong influence of “K-feminism” in the West. After Trump was re-elected, American social media began to adopt South Korea’s fringe 4B movement of the mid-2010s, known as the “Four Nos” movement, which is the abbreviation of the “Four Nos” movement. bean, Fly out of the mountain, biyenneand bisexualor “no marriage,” “no reproduction,” “no dating,” and “no sex with men.” However, while declaring oneself a feminist remains taboo in South Korea’s relatively conservative and predominantly patriarchal society, Western feminism has been developing for decades.

Against this backdrop, Kim provides a substantive overview of the intersection of the Korean feminist movement and the arts to aid the general reader, albeit laden with academic language. For example, King trusts audiences to decipher the differences between “non-modernism,” “anti-modernism,” “demodernism,” and “postmodernism,” nuanced concepts that can be further broken down into non-modernisms. expert.

Brief overview: Korean feminist art began in the early 1970s, marked by Biao Xian (Expression) Group, which emphasized femininity through craft methods such as textiles and sewing, resisted the modernist abstract works of the 1960s. The movement gained traction in the mid-1980s Belvedere Miller Inn Hu Club (Association for the Study of Women in the Arts), which honed a style of realism that reflected the condition of working women. By the mid-1990s, Xinshike (New Generation) Culture challenges the existing commercial art world by emphasizing issues of gender and identity. Korean feminist art in the 2000s reflected the globalized art world by beginning to incorporate intersectionality theory, a framework that explores how race, gender, and class, among other identities, combine to create systems of oppression and privilege.

Thematic chapters begin with a discussion of post-essentialism, the view that women are constructed by social processes, as opposed to first-wave feminism’s focus on biology, through the work of Yin Sunan and Zhang Pa. Although they are four generations apart – Yin So-nam is a pioneering feminist artist and radical activist who focuses on maternal themes in paintings, sculptures and installations, while Zhang is an emerging artist whose multimedia works subvert gender hierarchies and patriarchal norms—they all engage in a deep understanding of this conversation surrounding the image of womanhood. Highlighting this debate, which is central to the trajectory of feminism, provides a solid foundation for understanding further developments while emphasizing that these movements are not just about the time when they first emerged.

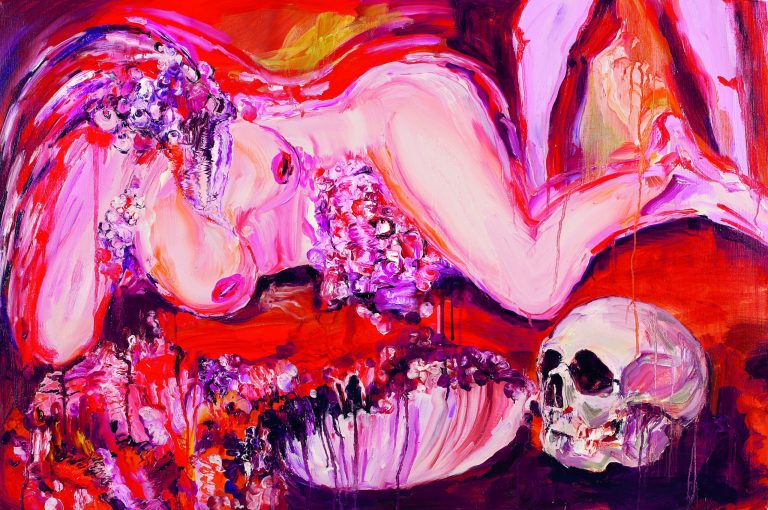

Next, Kim discusses body art through the work of Lee Bul, one of South Korea’s most renowned conceptual artists, as well as emerging figures Fi Jae Lee and Mire Lee, the latter of whom recently had her first exhibition at the Tate Modern Out of her Turbine Hall Commission piece. All three artists use robots and humanoid machines to explore how the female body fits into our posthuman, hybrid state, where identities are not bound by their physical containers but are instead constructed through informational patterns. King connects the artist’s aesthetics of the grotesque and the grotesque, breaking down the boundaries of gender binaries and normality.

Siren Eun Young Jung, Black Jaguar, and Nahee Kim examine queer politics, demonstrating the diversity of the category’s calls for inclusion, including the disruption of perceived normativity and broad civil rights. This chapter perhaps best exemplifies Kim’s advocacy of equitable intersectionality, showing how breaking down social classes associated with gender politics can make space for other vulnerable groups in society, including people with disabilities, refugees, and laborers.

Turning to sociopolitical themes, the book explores the work of Minouk Lim, Sanghee Song, Yang Ah Ham, and Ayoung Kim in relation to resistance art, critiquing the implicit truths of modernism and grand narratives associated with Western historical and mythological constructions, especially Works related to resistance art. Rapid urbanization in South Korea. These artists champion what King calls the “little narratives” of marginalized groups in society, including women, using research-based new media practices that incorporate neglected autobiographical stories of private and public grief. Lin’s “New Town Ghost” (2005) is an example. In this performance work, a female activist raps poetry over a loudspeaker and drums in Seoul’s busy Yeongdeungpo Market, singing the story of memories lost in the rapid development of commercialized “new towns.”

The chapter on the North American diaspora is also strongly political, highlighting the work of the late artists Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and Yong Soon Min, as well as Jin-me Yoon, all of whom immigrated as children. King borrows Homi K. Bhabha’s phrase “the genealogy of that solitary figure” to describe the displacement inherent in immigrant communities, which is a direct effect of globalization. For example, she discusses Min’s series decisive moment (1992), which includes six self-portraits overlaid with words and numbers that represent historical connections to her identity, including the 1960 student uprising, the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, and the 1992 Los Angeles riots. These artists also view Asian women’s displaced bodies as sites of erasure, violence, and instability, acknowledging unfulfilled desires to return to a unified Korea or to feel a sense of belonging in the United States.

Overall, this book provides a broad and in-depth survey of Korean feminist art, analyzing generations of female artists who intervened in the patriarchal norms of art history. With more than three decades of experience working in the field, including serving as director of the Seoul Museum of Art from 2012 to 2016, Kim stands out for her expertise as an early and enduring supporter of feminist art. Poet Kim Hyesoon’s essay aptly praises Kim Hong-hee’s “breathtaking” writing, which is attuned to the particularities of each artist’s practice. Adjusting overly academic language into more accessible terms may help attract a wider readership, but Korean feminist artist Still, these artists exemplify how these artists continue to break the boundaries of patriarchal conventions while hinting at a future in which feminist goals have long been achieved.

Korean Feminist Artists: Confrontation and Deconstruction (2024) written by Kim Hong-hee with contributions by Kim Hyesoon, published by Phaidon and available online or through independent booksellers.