Would you like a plastic shopping cart small enough to be pushed around by a doll? Just go to Google and search – you’ll find a lot of shopping carts like this. But not so long ago, artist Janet Olivia Henry recently pointed out that it’s not easy to find such objects on demand. She still remembers the thrill of the chase she felt decades ago as she traveled through Manhattan looking for toys to use in her sculptures.

In the 1970s, Henry began making her “Juju Boxes,” which were an assortment of toys—troll dolls, miniature plastic sinks and buckets, tiny bottles, mini mattresses, and more. Mindful of the West African practice of creating vessels filled with spiritual potential, Henry spent his spare time traveling through New York, scouring the stalls of street vendors and the aisles of toy stores. “I could walk across town to Chinatown for $10 and I’d come back with a big bag of all this stuff,” she said.

Eventually, she began creating “Juju Bags,” for which she took photos of the toys she had “accumulated” (which, she soon noticed, were not acquired) and placed the printed images inside stuffed bags of shredded dollars, paper etc. in plastic bags. The sacks, strung together like giant necklaces, collectively represent the characters in Henry’s creation, including one she names the “White Protestant Male.”

“When I do white protestant male,” she said, using the abbreviation of one of the “Juju Bags,” “I found that American culture has been copied. ” In 1994, when she gave the bag its counterpart, “White Protestant Male Lady,” she made sure to find a small plastic car that Henry believed was the ultimate symbol of bourgeois femininity. Due to the failure to do so at the World Trade Center Under FAO Schwartz to find it, Henry later went to a Spanish grocery store where she found her shopping cart and purchased it immediately.

This essay, and many like it by Henry, are about thorny systemic issues—how ingrained whiteness is in our material culture, and what it means for black women like herself to grapple with it. But rather than portraying these problems as too heavy to bear, Henry presents them as small and tangible. She does this in a light-hearted way, using the tools of the game in a way that makes it fun, disturbing, and entertaining.

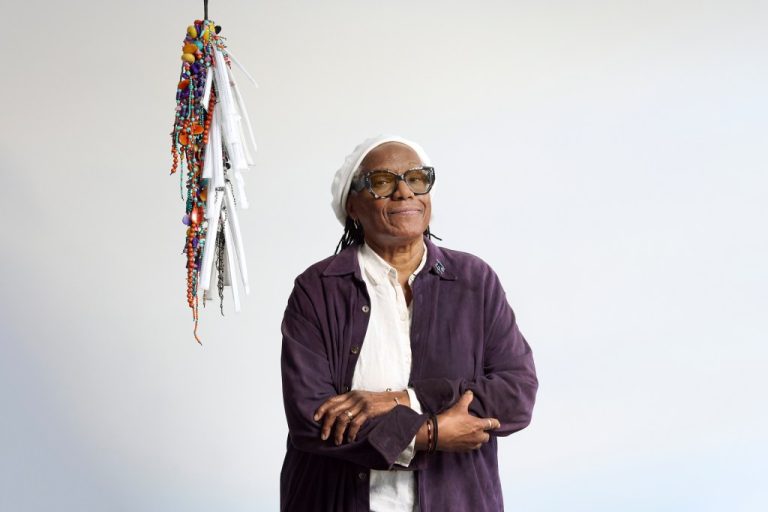

Janet Olivia Henry looks at crystal cabin (2024).

Photo by Christopher Garcia Valle for ARTnews

Her art has been exhibited in New York on and off throughout her career, but she received more recognition after she was included in Boston Iteration’s 2017 groundbreaking survey of black women artists active between 1965 and 1985 focus on.

2022, Henry’s 1983 diorama Studio visitwhich features a doll version of a white critic visiting her workspace, is on display at the Museum of Modern Art in a show about Above Midtown, an exhibition by Linda Goode Bryan The iconic New York gallery founded by Linda Goode Bryant, where Henry exhibited and worked. MoMA eventually purchased the work in 2023 as a gift from collectors Pamela Joyner and Alfred Giuffrida. In March of the same year, Henry held an exhibition at STARS Gallery in Los Angeles, followed by a solo exhibition in New York in 2024. The exhibition at Gordon Robichaux Gallery in New York is currently in its final days. Gordon Robichaux will bring Henry’s work to London next month for an exhibition at Hollybush Garden Gallery.

Henry, 77, talks modestly and digressively about her art. We met at Gordon Robichaux in mid-November. The artist, who commuted to Manhattan from her home in Jamaica, Queens, didn’t take me around her exhibition but spoke extensively about her years of teaching art to children. “I used to call myself a laid-back person,” she said. She talked about the joy of assigning art projects to her students. She then connected this to her own childhood, when she and her four siblings would draw on any bags they found around the house. Art, she explains, “makes you feel comfortable, and that’s my responsibility.” She adds with a smile, “I don’t want to make people feel scared.”

Installation view of “Janet Olivia Henry: Six Decades,” 2024, Gordon Robicheau, New York.

Photo courtesy of Greg Carrideo/Gordon Robichaux

She was born in New York in 1947 and lived in a residential neighborhood in East Harlem. Her father served in the West Indies in World War II and later raised a family on the GI Bill. She already knew she was an artist before she went to art school—Henry recalled dragging her siblings around to make art with her.

When she was nine, her family moved to Antigua. Henry said the radio broadcasts ended at seven o’clock, so, she said, “we learned to entertain ourselves.” She listened to her cousin recount family history, which gave Henry a keen interest in narrative construction. Although Henry and her family only lived in Antigua for three years before returning to East Harlem, the island nation left its mark—a “Juju Box” circa 1976, Gordon Gordon Robichaux’s show featured bows on the shoes Henry arrived in. Live back from there.

As a teenager, Henry attended an arts-focused high school in Manhattan, now called LaGuardia, but she did not study art. “Girls are starting to get into fashion,” she said. “I was interested in it.” But she wasn’t the best at the draping exercises that fashion students must perfect, and she had little taste for assignments that required “very bland, distorted drawings.” All the artists she met over the years left a more lasting impression on her, although she said many of them were white.

Janet Olivia Henry, JuJu box (back from Antigua),about. 1976.

Courtesy of Gordon Robicheaux

Henry later attended the School of Visual Arts and the Fashion Institute of Technology, but from there her career path was very different from what a practicing artist might have expected. She doesn’t have an MFA—“I’m the last of the Mohicans,” she once told an interviewer—and is arguably prolific as a children’s educator, which she has been doing since the 1960s. this profession.

She steadily produced art while earning the attention of sculptor David Hammons and a spot in the 1981 residency program at the Studio Museum in Harlem. At the Studio Museum, she became acutely aware of how power worked within the walls of art. mechanism. “The contrast between the administrators and the people I saw on the street became very stark,” she said. Then, in 1982, she showed her “Juju Boxes” at Just Below Midtown Gallery, a gallery known for its focus on black artists.

A few years ago, Henry attended the opening of Above Midtown and was inspired again. “I said, ‘If I never show up here, I don’t care.’ Just knowing it exists gives me something to look at,” she said. “There are people trying all kinds of things. Some of them, frankly, are just crazy.” Those include Hammons, Senga Nangudi and Howardena Pinder.

When Linda Goode Bryant started Just Below Midtown in 1974, artist Romare Bearden told her she needed $50,000 to launch her own gallery . Good-Bryant never had that kind of money and often described struggling to keep her space open. (The gallery eventually became an alternative space and closed that way in 1986.) Worried that Just Below Midtown might close, Henry began volunteering to help out in any way she could, becoming what she calls a “peon” at the gallery.

Janet Olivia Henry, White Protestant Male (WPM)1983.

Courtesy of Gordon Robicheaux

“When you find something beautiful, you don’t want to let it go,” Henry said. “But it’s more than that. It’s a whole way of thinking. I want to make that my environment.” In addition to showing there, she’s helping to develop the environment through design black currantis a journal edited by Greg Tate and features works by Hammons, Camille Billops, and others.

A comprehensive artistic network helps Henry keep going. For example, in 2002, Henry exhibited a group of sculptures at PPOW, which consisted of dolls, baubles, etc., forming words such as “entitled”. She once credited photographer Carrie Mae Weems, who was on the PPOW roster at the time, for winning her the opportunity to exhibit at the gallery.

But Henry isn’t as famous as many of her colleagues – and that doesn’t seem to stop her. She continues to teach and create her art, including New York Fantasyis a 15-foot-long Central Park sculpture made entirely of Lego bricks (“interlocking plastic bricks,” as she prefers to call them).

Henry also uses IPB to build walls crystal casita (2024), a diorama from Gordon Robichaux’s exhibition in which a black female doll (a stand-in for Harvey himself) sits on a table. There is a mini Tupperware box filled with sliced plastic watermelon; at her feet lies a pair of teeny-tiny sneakers. Behind her, a pyramid of scooters awaits their future use, presumably in an art installation. As we spoke, Henry sometimes glanced at the little doll, smiling, perhaps wondering what she was going to do next.