When Liliane Lijn moved to Paris in 1958, she found herself sitting at a table in the famous Surrealist café. By then they had become “a bit bored,” she recalled years later. André Breton launched the movement in his 1924 manifesto, which thereafter “expelled all the most interesting people.” So did the Nazis.

Lijn was only 19 when she arrived on the scene, so few people in the café actually listened to her ideas. Still, there’s a lot to take in. Lane would eventually become famous for her kinetic sculptures and works that straddled science and art, but everything she did over the next half century was owed to her exposure to Surrealism. All of her work begins as a drawing, a testament to her belief that graffiti and automatic writing in the Surrealist tradition are ways of tapping into the subconscious.

Paintings from the Paris years open the retrospective exhibition “Liliane Lijn: Arise Alive”, which will be on display at the mumok Vienna until May 4. The exhibition is organized in collaboration with Haus der Kunst in Munich and will travel to Tate St Ives – a very dynamic moment. The New York-born, London-based artist, now in his 80s, is long overdue for recognition.

Lillian line: come alive1965.

Photo Richard Wilding. Courtesy of the artist and London Rodeo.

The show’s title comes from one of Lijn’s Poetry Machines (1962-68), in which she printed words on cones and then made them spin on a turntable. The text seems to move slower near the bottom because the cone is wider and the letters travel a longer distance. come alive (1965) rotated the words “emerge” and “alive,” which are difficult to parse when rotated. “Alive” is how Lijn often says she wants her works to feel; that’s part of the reason she makes them move.

How did Lane cross over from surrealism or science? This seems an unlikely and even unsettling path. But take yourself back to the early 20th century: at the same time that senseless world wars prompted the Surrealists to lose faith in reason, quantum physics emerged to show us yet another way in which common sense is useless.

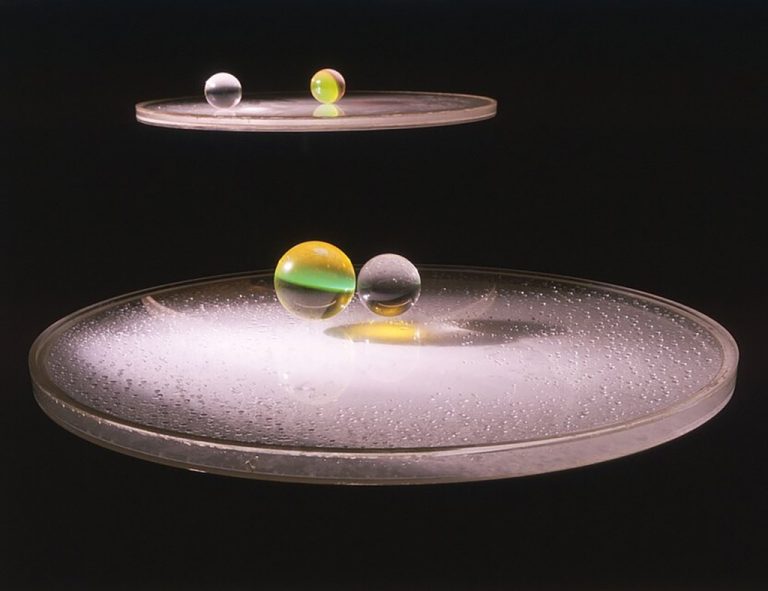

Quantum physics inspired Lijn’s magnum opus, liquid reflection (1968). She created the kinetic sculpture to explore how light behaves as both particles and waves at the same time – a phenomenon that is notoriously impossible to observe. Therefore, Lijn set up two pairs of acrylic marbles to resist two opposing forces. First, she placed them on a turntable that contained a hollow, concave disk filled with a viscous liquid. Then, she dramatically lights them up and spins them around.

About these competing forces: The rotating table creates a centripetal force that pushes the ball to the outside. At the same time, centrifugal force attracts the ball to the depression in the center of the concave disk. But it’s not didactic or technical: it’s enjoyable and fascinating. Each ball behaves differently and is pulled in different ways. It’s even easy to personify these balls because of their unpredictable relationship: they dance, circle each other, and cling to each other; then one of them spins away with purpose, while the other stays in place. This is a soap opera starring Pinball.

Lillian line: A union of opposites: Beast Lady and War Woman1986.

Photo Thierry Barr. Courtesy of the artist and London Rodeo.

Lane would return to the cone, which she had come to see throughout her career as the gray cone symbolizing the Greek goddess Hestia. She saw cones like this after she moved to Greece and married kinetic artist Takis. The series “Light Koans” (1968-2008) consists of luminous loops of lines that dance hypnotically as the cones rotate. In 1987, Lijn said: “I hope that the goddess will be resurrected through my work.” For Lijn, spirituality and science are both fascinating mysteries. She reduces these mysteries to their essential forms, making them easier to understand and appreciate without diminishing the sense of inexplicable awe.