There are many memorable moments in the new biography Candy Darling: Dreamer, Idol, Superstarby critics and former Village Voice Columnist Cynthia Carr. Sources say that Peter Hujar, whose prolific and sensitive record of queer New York in the 1970s and 1980s included a striking photograph of Darin on his deathbed, died 13 years later in the same room when the hospital floor was converted into a care center for people living with HIV. Carr also reveals that Darin’s funeral took place in the same room at Campbell Funeral Home on the Upper East Side as Judy Garland’s—a Hollywood connection Darin would have appreciated.

But perhaps most striking is a passage at the beginning of the book. We learn that in the 1950s, actress Christine Jorgensen, one of the most famous transgender women of the 20th century, moved into a house in Massapequa Park, Long Island, a 30-minute walk from Darling’s childhood home. “Candy would walk there and then pace in front of the house, hoping to see Jorgensen appear,” Carr wrote. “But she never did.”

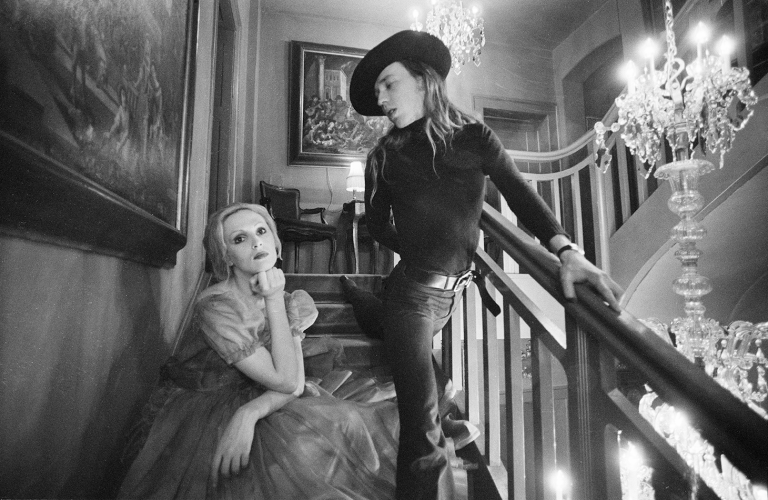

Candy Darling went on to star in 10 films, most notably in Andy Warhol’s 1971 film Women in Resistance (directed by Paul Morrissey), and plays by Tennessee Williams, Jackie Curtis and Tom Irons. She was the subject of Walk on the Wild Side (1972), probably Lou Reed’s best-known song, and she also inspired the music and lyrics of the Rolling Stones. She was not only photographed by Hujar; Richard Avedon, Laura Rubin and Francesco Scavolo, among others, and she also appeared on After Dark Magazine, in Esquire, Women’s Wear Daily, Movies and TV seriesAnd multiple issues interviewAlthough she died of lymphoma in 1974 at the age of 29, her legacy has impacted multiple generations, influencing artists from Greer Lankton to Anohni to St. Vincent.

But Carr’s story of young Darin is so vivid—living in the brutal conditions of Long Island (where Levittown was born), quietly hoping to meet a trans person in person, perhaps seeking some of Jorgensen’s knowledge and experience in a world where most people refused to acknowledge the possibility of trans people, and perhaps hoping to be as glamorous as she was (Jorgensen turned her public coming out into a decades-long career as a performer, public speaker, and activist). But even without meeting her, Jorgensen must have made her feel that Darin was not alone, that there was precedent for her existence, and that people could achieve the fame she dreamed of.

Given Darling’s fame, it is remarkable that 50 years after her death there has still been no biography. Beautiful dearbut the entire film is rife with casual and intense transphobia. The influence of Darin’s close friend and unreliable narrator Jeremiah Newton on the film sometimes feels overbearing, although he does deserve credit for becoming the custodian of Darin’s physical archive and ashes when Darin’s mother, Theresa Slattery, tried to get rid of them. He also went on to record countless interviews with people who knew Darin, creating an archive that Carr felt was crucial to her writing the book.

Carr is careful to point out that Darling herself was an unreliable narrator, whose confusions were widely acknowledged by those in her life, whether in tall tales about how she spent a night or in fictional accounts of her upbringing. But the author emphasizes that Darling not only had to forge her own existence but also had to confront the painful contradiction that her fame was often associated with the public’s categorization of her as a drag queen or “transvestite” rather than the woman she knew herself to be.

Unlike the documentary, Carr’s biography is deeply researched and deeply empathetic. Readers witness the relentless transphobia Darin faced, while also learning that her fiction and dissembling were both a coping mechanism and a refusal to accept the limitations others tried to impose on her. Darin grew up without a home of her own and with little money, her life was precarious even as she walked into some of New York’s most exclusive parties with Warhol at his most famous arm.

Still, the fact that she was a thin, white woman who conformed to the beauty standards of the time afforded her opportunities that were unavailable to many of her non-white, transgender peers or those whose bodies didn’t conform to entrenched and unattainable beauty standards. I don’t point this out to criticize Darin; she survived with everything she had. Rather, I bring this up to criticize a discriminatory society and, by extension, the historical record. This book offers a rich, nuanced portrait of how she defied that society and did so with great style and panache. It’s vital to have full, compelling portraits of people who break new ground, proving that we can be both flawed and extraordinary. Here, we learn without a doubt that Darin was an extraordinary woman.

Candy Darling: Dreamer, Idol, Superstar Written by Cynthia Carr (2024), published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, available online and through independent booksellers.