Art

Maxwell Raab

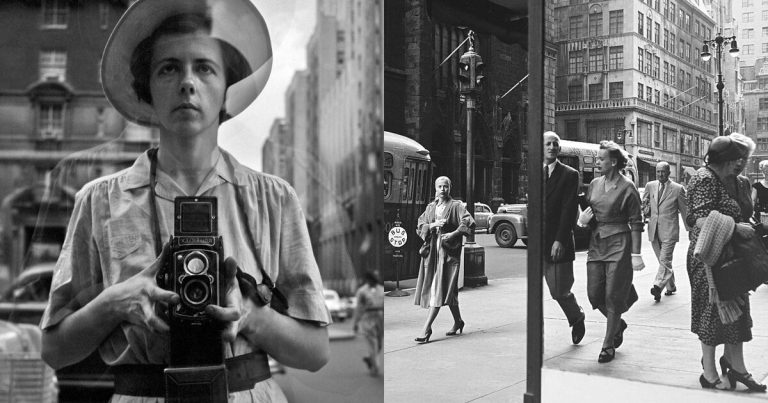

Vivian Maier, Self-portrait, Chicago, Illinois, 19561956. © Estate of Vivian Maier. Courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

It was with the quiet click of her Rolleiflex camera that Vivian Maier captured the world around her in permanent frames. From bankers to homeless people sleeping on park benches, to couples embracing, and often even herself: the range of subjects she photographed was extraordinary in the more than 150,000 negatives she shot during her lifetime. For nearly five decades, Maier meticulously documented the life around her wherever she went. Yet her works remained private, stored in boxes without the funds or resources to develop them.

By the time of her death in 2009 at the age of 83, her collection of negatives had been virtually unknown. However, in 2007, her life’s work was auctioned off at a local thrift store in Chicago to local historian and collector John Maloof. Intrigued by her street photography, Maloof developed the negatives one by one, gradually publishing Maier’s extensive archive on Flickr. These forgotten photos lay undeveloped for decades, sparking an unprecedented enthusiasm for Maier’s work just months after her death.

Vivian Maier, installation view of “Unseen Work” at Fotografiska New York, 2024. Courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

For the first time, part of Maier’s vast archive is on display at Fotografiska in New York, her birthplace, in an exhibition called “Invisible Works,” which runs until September 27. Curated by Anne Morin, director of cultural management company diChroma Photography, the exhibition was originally presented in a different format at the Musee Luxembourg in Paris in 2021. It features more than 200 thematically arranged works spanning the 1950s to the 1990s, including color photographs shot with Leica, Super 8 film, and various sound recordings. This homecoming exhibition places Maier’s work in the urban context that shaped her vision and consolidated her legacy – increasingly important in an age of social media and self-awareness.

“Vivian Maier is a phenomenon today because [the] “This self-portrait resonates with the selfie culture we see today,” Morin said. “The identity crisis we see with social media, and the abundance of selfies, is echoed in Vivian Maier’s work. Maybe 30 years ago, she wouldn’t have been as famous or as interesting because selfies weren’t as important back then.”

Early Years in New York City

Vivian Maier, Chicago,Illinois, ndn.d. © Estate of Vivian Maier, courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Vivian Maier, Self-portrait, New York, 19551955. © Estate of Vivian Maier, courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Maier was born in 1926 to a French mother and an Austrian father. Maier led a simple life as a child. After her father died, Maier lived for a time in New York City with her mother, Marie, and photographer Jeanne Bertrand. Later, they lived for a short time in a small French village not far from her mother’s home. At the age of 23, Maier received her first camera, a Kodak Brownie, as a gift, and began to experiment with various photography techniques.

In 1951, Maier returned to the United States and found work in a sweatshop and later as a nanny in Southampton, Long Island. There she began a long and obscure career behind the lens, visiting museum exhibitions or spending time in the cinema during her free time in New York City. A year later, Maier bought her first Rolleiflex camera. In the city, she began to take pictures of everyday life, such as a humorous picture taken in 1953 of two old men leaning over a hose, or a sentimental picture of a couple looking at the New York skyline from a ferry.

Vivian Maier, New York, New York Around 1953, Circa 1953. © Estate of Vivian Maier. Courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Vivian Maier, Grenoble, France, 1959 1959. © Estate of Vivian Maier, courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Maier’s earliest photographs, including a 1953 portrait of a child standing upside down in a mirror and a 1954 self-portrait in a department store window, highlight Maier’s innate ability to compose images quickly. The compositions are full of small quirks and subtle camera tricks that make her records both humorous and unique.

“She had the ability to bring out the extraordinary in ordinary life,” Morin said.

Family nanny, street photographer

Vivian Maier, installation view of “Unseen Work” at Fotografiska New York, 2024. Courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

A new chapter in Maier’s life began in 1956 when she moved to Chicago’s North Shore to work as a nanny for the Gainsburg family. There she had a darkroom where she developed photographs and processed black-and-white film. However, the most significant influence on her during this time was the children she cared for.

“If Vivian Maier hadn’t been a nanny, if she hadn’t been around children, maybe she wouldn’t have had such a huge imagination: playing, inventing, telling stories,” Morin said. Maier’s work, especially from 1956 to the 1970s, is full of this childlike impulse. Her photos, whether they capture a poster of a woman sticking out her tongue or a bystander of a fight between a policeman and a woman, feel new and novel. In the crowds of the city, she seems to be interested in everything and everyone, as if seeing it for the first time.

Vivian Maier, Chicago, Illinois, May 16, 19571957. © Estate of Vivian Maier, courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Vivian Maier, Chicago, Illinois, 1960scirca 1960s. © Estate of Vivian Maier, courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

She often took the wealthy children in her care to poorer or industrial areas of Chicago to broaden their horizons. She also photographed these environments, such as her 1963 photo of three children playing in a concrete pipe. Her photos engage with often overlooked elements of the urban environment, capturing moments as the viewer encounters them. As Morin says, “She had a way of embracing the world at her fingertips, collecting small stories—little things—that she found on the street or anywhere.”

Self-portraits through the decades

Vivian Maier, installation view of “Unseen Work” at Fotografiska New York, 2024. Courtesy of Fotografiska New York.

Self-portraits are a hallmark of Maier’s photographs and are among the most striking works in the Invisible Works. Her first self-portraits, while she lived in New York, depicted her standing in front of a window or mirror. Later, in Chicago, she experimented with space and composition. Some works, such as her Untitled Self-Portrait from 1956, use a bathroom mirror to capture herself. To infinity. “No other photographer has really thought so deeply about how to present himself,” Morin said.

She turns the camera on herself, often with a serious look on her face, as she struggles with her identity, which is also reflected in her shadow. In these portraits, she seems to be gradually forming an idea of who she is. “Photography is like the title of Virginia Woolf’s book. A room of your own,And is [Maier’s] “She had her own room,” Maureen said. “Photography was where she built her identity, where she was free, where she could create her personality outside of this little room, and that was her photography, her language.”

Invisible Street Photographer

Vivian Maier, Self-portrait, New York, 19541954. © Estate of Vivian Maier, courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Vivian Maier, Untitled, circa 1955 circa 1955. © Estate of Vivian Maier. Courtesy of the Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Like many photographers before her, Maier walked the streets of Chicago and New York. Her work is particularly moving among her contemporaries because of the underrepresented in her photographs, whether it’s immigrants in New York or elderly women walking through the streets of Chicago. While traveling through the city, she documented poverty, demolished landmarks, and everyone from the lower to upper classes. In many ways, the street is the great equalizer.

Overall, Meier is in a similar situation to these people: a victim of the American Dream. ” [Maier and her subjects]” said Maureen. She lived as the daughter of immigrants and worked throughout her life, producing a large body of work. However, in her old age, she became impoverished and was nearly evicted from her small Chicago apartment before the three children she was caring for rescued her and placed her in a nursing home. She sold all of her work to pay the bills and died suddenly in 2009, before her work was appreciated.

Maier dedicated her life to photographing ordinary people behind the lens, capturing the city’s untold stories with an eye that gave dignity to her subjects. In this way, she preserved a moment in time and confronted her own place in it. “She was part of the dark side of the American dream – the invisible, the invisible,” Morin said.

Maxwell Raab

Maxwell Rabb is a staff writer at Artsy.