CHICAGO — In 1968, Christina Lamberg exhibited 16 small, strange, detailed paintings of women’s hairstyles. Each square painting depicted a white woman’s head, seen from behind, her black hair manipulated by a feminine-looking hand, against an acidic gray-green background.

She is only 22 years old, but she already knows a lot about art. Christina Lamberg: A RetrospectiveThis is the first comprehensive presentation of the work of the Chicago Imagists, as they are often called but who, in my opinion, are the most exciting, in nearly thirty years. A similar exhibition is also underway in the museum’s prints and drawings galleries, Four Chicago Artistsincluding work by another of my favorite artists, Barbara Rossi, who was a close friend of Ramberg. Both belonged to a generation of local creative artists, many of whom studied and taught at the Art Institute of Chicago, exhibited at the Hyde Park Art Center, collected folk and non-Western art, and regularly frequented the open-air Maxwell Street Flea Market.

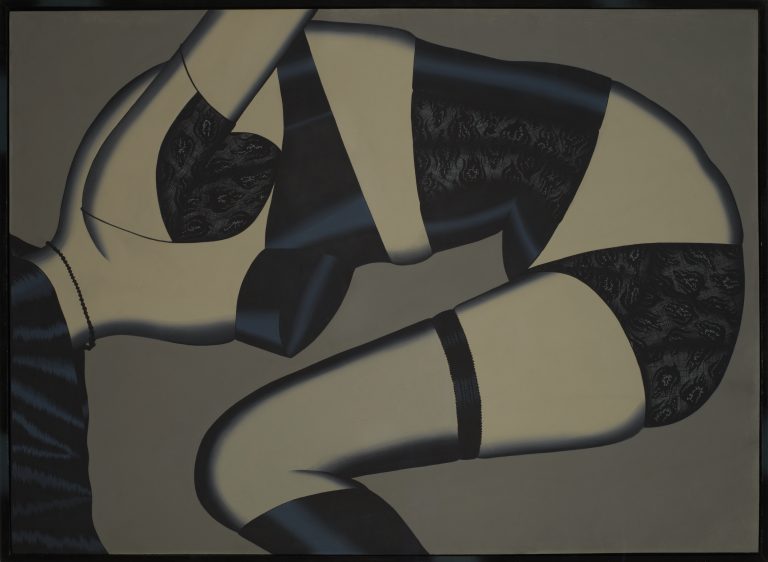

The Ramberg retrospective, co-curated by Thea Liberty Nichols and Mark Pascale and scheduled to be shown in Los Angeles and Philadelphia, opens with Hair and other works from her art student days. In each of these works, there are a host of elements that Ramberg would refine, deepen, and deepen throughout her career: the shiny blue-black hair of romantic comics, the weirdness of fragmented, faceless body parts, the ability of one thing to mimic another, the allure of perfect line and invisible brushstrokes. She constantly exerts control over bodies, often women, as in her iconic photographs of the era, which show women squeezed into lace corsets, satin corsets, and knee-high socks, with every bit of sheen and line rendered individually, every bulge of flesh impossibly smoothed, every torso twisted to fit the frame. Two Piece, 1971, shows a tuft of spiky hair under the armpit, a rare example of Ramberg letting hair flow freely. More typical are “Black Widow,” with her shiny locks tightly coiled and flowing so freely that they could be mistaken for something else, and “Waiting Lady,” with her elegantly tied black lace armpit guards.

I learned that, before the advent of deodorant and dry cleaning, armpit guards were used to protect delicate garments from excessive sweat. But what is a French tickler? Turns out it’s a condom with ribbed protrusions for extra pleasure. They’re the ostensible inspiration for a series of tall, narrow paintings that Ramberg made in 1974 that are unmistakably phallic but mostly just deeply weird: imagine a giant finger, wrapped in lace, tightly wrapped around sleek hair. The hair can be used for ties or real hair from your head, but it can also be a lot of other things: Throughout the ’70s, Ramberg depicted hair candies made from tiny paper pads, corsets and urns made from shimmering brown hair, and even carved chair backs and lamp bases made not from wood but from styled hair. She hand-painted many of the frames, sometimes in the same style as the hair, sometimes with simulated wood grain or marble. There’s even a series of life-size headless torsos, not quite human but definitely terrifying, whose genitals, bellies and severed arms have been bound in these things (for pain, for pleasure, for protection – it’s not clear). Their unbound skin is covered in fishing netting that, when worn, looks a lot like pubic hair.

Why hair? Well, hair isn’t the only thing that’s reassembled in Ramberg’s work, though he does it often. Individual pieces of clothing, specific body parts, and a wide variety of patterns can be reassembled in any number of ways, most vividly in three large, unusually colorful paintings from 1981. Each painting presents a figure composed of clothing, with a checked coat representing the upper body and arms, a pair of red pants and a pink button-down shirt hanging between the legs like a penis, and an inverted pair of yellow pants becoming a chest. These bodies are composed of other bodies, all of which make up the clothes. The clothes are appropriately New Wave, all boldly patterned and with padded shoulders, helping to shift the tone from horror to comedy. Three small paintings from the previous year that depict women’s clothing take the opposite tack: These dresses are sewn not from fabric but from cuts of meat—a cross between a butcher’s drawing and a sewing pattern. Ramberg, who often sews clothes for her six-foot-one, hard-to-fit body, knows what she’s doing.

Artists, like artworks, are ultimately elusive, but Ramberg left behind an archive that offers plenty of clues to the sources and personal motivations of her work. Some of it is on view, including her “Doll Wall,” a thrift-store-find installation that took up an entire wall of her apartment, and color slides she took of medical illustrations, tattoos, chimneys, gemstones, mannequins, crosses, and patterns on floors and doors. The pages of the scrapbooks she made with her later husband, the artist Philip Hansen, are filled with cutouts of hair and hands from comic books. Sketchbook pages neatly display the endless variations of stylized bras, headbands, and other elements in her finished paintings. The exhibition catalogue reproduces a wealth of additional archival material, as well as Judith Russi Kirshner’s revealing essay on Ramberg’s diaries, which were used for family records and red for studio notes. Like many artist mothers, she was pressed for time and placed great value on the time she devoted to her art. She also wrote about her sexual fetishes, including bondage. All of which is to say that if S&M, clothes hangers, superhero comics, and doll parts come to mind when you think of her 1975 painting Broken, know that the same probably applies to this artist.

In 1983, Ramberg stopped painting, declaring herself “stuck in trouble,” and devoted herself full-time to quilting, which she had been practicing in her spare time for years. The five works on display share the same pattern, figure, and continuity as her famous paintings, but lack the focus on image. Despite the curator’s claims, this absence seems to me at least as different from her previous formal art as it is, and far less fascinating. When she returned to painting in 1986, she produced scribbled black-and-white drawings of tower blocks. A few years later, she was diagnosed with Pick’s disease, a rare neurodegenerative disorder, which forced her to stop working and eventually commit suicide in 1995 at the age of 49.

Christina Lamberg: A Retrospective The exhibition will be on view at the Art Institute of Chicago (111 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL) through August 11. The exhibition is curated by Thea Liberty Nichols, Associate Research Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Mark Pascale, Janet and Craig Duchossois Curator of Prints and Drawings.

Four Chicago artists: Theodore Halkin, Evelyn Statsinger, Barbara Rossi and Christina Ramberg The exhibition is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago (111 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL) through August 26. It is curated by Mark Pascale, Stephanie Strother, Research Assistant in Prints and Drawings, and Kathryn Cua, Curatorial Assistant at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.