Art

Olivia Horne

Mary Cassatt, Mother and Child (Mother’s Kiss)1896. Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In a museum, this behavior might be inelegant, but it’s understandable if you want to get up close and personal with Mary Cassatt’s incredibly soft, textured paintings. Mother and Child (Mother’s Kiss)A particularly intriguing candidate, the 1896 work on paper shows the plump cheeks of the figures (probably a mother and daughter) gently squeezed together; strands of silky hair tied into bows and chignons; and wisps of pastel streaked across the paper like taffy.

It is here, in one’s imagination, that Cassatt’s work begins and ends—in a cocoon of domesticity, or what art historian Edgar Richardson once described as “an eternal afternoon tea.” Mother and Child (Mother’s Kiss) Part of the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), which is exhibiting the latest works by the American Impressionist through September 8, “Mary Cassatt at Work” aims to subvert the notion of Cassatt as a painter of pastoral scenes. As exhibition co-curator Laurel Garber said in an interview, it stems from a desire to “bring contemporary issues and conversations to the material.” “There are so many ways to revisit her scenes that have…ossified into — I think — tired interpretations.”

Mary Cassatt, Little girl in blue armchair1877–78. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Mary Cassatt at Work is grounded in a contemporary feminist sensibility, namely a sensitivity to the historical undervaluation of so-called “women’s work.” We are reminded that domestic labor was essential: when Cassatt painted, she also painted workplaces. More importantly, since women of Cassatt’s socioeconomic status often viewed painting as a hobby, highlighting the professional nature of her practice also adds an important feminist perspective. When Cassatt depicted her home as a workplace, she was working herself—not just engaging in a bourgeois hobby, a more socially sanctioned undertaking.

Cassatt was, of course, a woman ahead of her time, and her work has been studied through the lens of feminist art history for decades. Today, fourth-wave popular feminism, keen to idolize individuals, might be tempted to hold her up as a poster child for feminism. The exhibition has more modest aims; it largely avoids explicitly labeling Cassatt a feminist. Nonetheless, it reveals aspects of the artist’s life and work that resonate with contemporary ideas about female empowerment, both on an individual and collective level.

Modern Painters, Modern Life

Mary Cassatt, installation view of “Mary Cassatt at Work,” Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2024. Photo by Timothy Tiebout. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Cassatt’s personal highlights were remarkable. Born in Pennsylvania in 1844, she studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia before moving abroad to continue her art training. In Paris, she befriended Edgar Degas and was eventually invited to exhibit with the Impressionists not once, but four times. She was the only American to do so, and one of very few women. In 1904, Cassatt became the second female artist to receive the French Legion of Honor from the French government. In today’s terms, she broke the glass ceiling.

Impressionism was the painting of modern life, and Cassatt’s own life was thoroughly modern. Though she often painted infants, the artist herself never married or had children. The exhibition takes pains to underscore her unwavering commitment to her professionalism—from 1878 onward, her family insisted that she be self-sufficient. “I am independent!” Cassatt once wrote, in a quote that now hangs on a gallery wall at the PMA. “I can live on my own, and I love my work.”

Utopian Women’s Collaboration

Replica of Mary Cassatt, Modern Women1892–93. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

One of the most important works of Cassatt’s career, Modern Women (1892–93) is described by art historian Nicole Georgopulos in the exhibition catalogue as the artist’s “great work on the emancipation of women.” Commissioned for the Women’s Building at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, the large mural depicts a Garden of Eden where women work together to harvest and spread the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Modern Women It survives only as a photograph, but its allegorical vision of female education reveals Cassatt’s interest in collective patterns and networks of knowledge.

These themes appear on a smaller scale Fruit pickinga lithograph produced the same year as the World’s Fair. Rendered in a verdant botanical setting, the painting depicts a woman on a ladder handing picked grapes to a child held by another woman. Here, Cassatt recasts the image of Eve and repositions knowledge as a source of female power rather than a source of sin.

Women’s work

Mary Cassatt, In the comprehensive version1890–91. Image courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Mary Cassatt, bath1890–91. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Mary Cassatt’s world is full of maternal gestures (titles include Mother’s Kiss, maternal love) — but in many cases her images were fictional. Cassatt’s “mothers” were often paid models, and she also frequently depicted “pink-collar” workers, such as wet nurses and hired care workers.

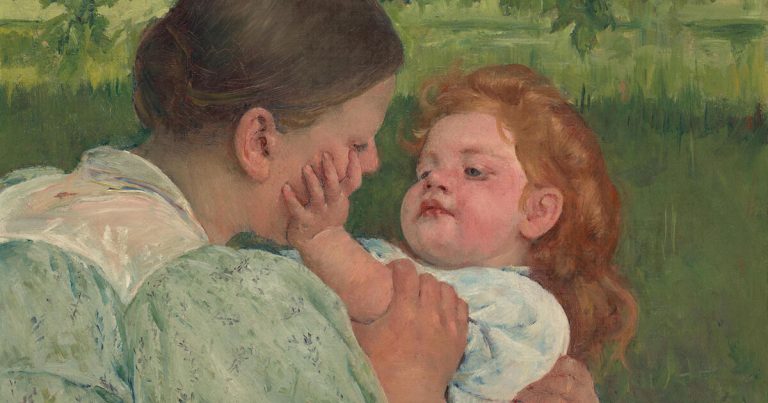

“Mary Cassatt at Work” suggests that the sentimentality of these images is undercut by Cassatt’s persona, as well as her compositional choices. As a result, they touch upon the reality of motherhood, real or fictional: it’s all work. maternal love (1896), Cassatt emphasizes the physicality of caring for a child. The painting’s adorable subject, a rosy-cheeked toddler with strawberry-blond curls, appears to be shoving her thumb into the mouth of her caregiver, who clutches her arm in restraint. “The question we wrestled with was, ‘Is that a good title?’ ” Garber’s co-curator Jennifer Thompson said of the painting during a tour of the exhibition. “Is there any caressing in the painting?”

Mary Cassatt, maternal love1896. Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

While Cassatt, due to her gender and class, was unable to access many of the spaces her male Impressionist colleagues frequently painted—street scenes, Parisian nightclubs, and the like—Garber points out that Cassatt wasn’t just painting what was accessible. These domestic scenes weren’t just observed, they were actively staged. This comes across in a letter Cassatt wrote to her friend Louise Havemeyer, in which she describes “the difficulty of posing the model, choosing the color scheme, expressing the emotion, and telling the story!”

“She chooses to cut scenes in very interesting ways, or [the way] “She enlarges and brings to life the figures within the frame,” Garber said. “I found that really speaks to the challenge she faced in capturing the intensity and physicality and the impact and tension of these scenes.”

Cassatt

Mary Cassatt, woman holding sunflowercirca 1905. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Mary Cassatt, on the balcony, 1878–79. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

While Cassatt’s writings and biography indicate an interest in women’s advancement, there is little evidence that she was associated with early feminist thinkers or the organized women’s movement, and she lived most of her adult life in France. However, she became involved in the suffrage struggle across the Atlantic. In a 1914 letter to Havemeyer, she advised her friend to “work for suffrage. If the world is to be saved, it will be women who will save it.” In 1915, Havemeyer organized an exhibition at a New York gallery, and Cassatt contributed 29 works to the exhibition to raise funds for the suffrage movement.

A work not on view in the PMA exhibition but included in its catalogue further underscores Cassatt’s commitment to the cause. woman holding sunflower (c. 1905) captures a familiar scene from Cassatt’s work—a seated woman with a child in her lap. The most striking feature is the large, bright sunflower pinned to the woman’s skirt. The flower was incorporated into the official image of the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1896, and as historian George Prowse has pointed out in recent scholarship, its suffrage symbolism would have been widely recognized at the time.

Modern viewers might be inclined to view the flowers as purely decorative. But like much of Cassatt’s work, this painting holds layers of meaning beneath its soft, beautiful surface.

Olivia Horne

Olivia Horn is Artsy’s deputy editor-in-chief.