June Leaf, a beloved artist whose mesmerizing, uncategorizable work explored the limits of the human body, died Monday in New York. She was 94. New York Times She had reportedly been battling stomach cancer.

It is almost impossible to pin down Leve’s work to a specific interest, as it takes many forms: unusual remakes of famous art historical images, surreal monuments to women, self-portraits, mechanical sculptures of recluses in small spaces, etc. Leve’s obsession with the human figure permeates all of his work, even at a time when abstraction was being revered by critics.

Although Liv’s work has almost always won acclaim, she has never fully fit into the mainstream artistic mold, which may have cost her more visibility. But she doesn’t seem to care too much whether people know how to categorize her.

For some, what makes Leaf’s art so significant is that she invests so much energy in the possibilities of the image. Critic Barry Schwabsky once wrote: “What constitutes June Leaf’s genius is also what makes her a kind of retro or anomaly, her work looking back through the work of Giacometti and Picasso to the primal impulse to create images.”

Leaf herself might agree, she said Allergic 2016. “I work with these characters until I am free of them. At least, I think so. I have been making art since 1948, but I don’t have a coherent theory yet.”

June leaves, Angel2022.

Photo: Dario Lasagni/Ortuzar Projects, New York

Liv is best known for her sculptures, which animate when activated by viewers. Some of these pieces contain triggers that, when triggered, enact everyday scenes—for example, a walking woman, represented here by a blunt-spoken metal figure. Other works take the form of scrolls that can be turned with a crank. Still others focus on specific body parts: hands, heads, torsos, and so on. Liv’s goal is to “sculpt people from the inside out.”

At one point, someone asks her why she’s so obsessed with the body, and Liv seems to think it’s closely tied to her experience as a dancer. “I see myself as a dancer who makes art,” she says. “Or a pilot who makes art.”

June leaves, Painting in motion2020.

Photo: Dario Lasagni/Ortuzar Projects, New York

June Leaf was born in Chicago in 1929. She says her earliest artistic memory dates back to when she was 3 years old, playing with a piece of fabric and decided she wanted to make everything with her hands. She then asked her mother to draw her a shoe, and the resulting image sparked her love for drawing.

At age 18, Leaf enrolled at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s School of Design, where she learned the experimental painting strategies devised by the school’s founder, László Moholy-Nagy. Although she was excited by the techniques being taught, she found herself more interested in visiting artists than actual classes, so she left the academy with plans to become an artist herself.

June leaves, Untitled (Coastline and Figures)circa 1980s.

Photo: Timothy Doyon/Ortuzar Projects, New York

In 1948, she set off for Paris. Much to her surprise, people began to compliment her work, encouraging her to pursue more experimental projects, such as painting on bathtub tiles. Some thought she was insane—which she was not, as a psychiatrist confirmed—but she persevered, realizing that she had now found her calling.

She returned to Chicago, where her work began to attract attention from local artists like Leon Golub, who personally confirmed to her mother that she was on the right track. She eventually earned her master’s degree from the academy in 1954. Four years later, she received a Fulbright scholarship and traveled to Paris a second time. She had taken life classes at the Louvre, but she worried that she would be overwhelmed by the old masters she was copying.

In 1965, Leaf created her first sculpture. Vermeer BoxIt’s a three-dimensional recreation of an actual Vermeer painting, with some contemporary elements added, including a coin. “I couldn’t do that in a painting, so I had to try to use other dimensions,” Liv told Allergic“That explains why I use materials. I am a painter who must have a tactile experience of the world. I have to take a circuitous path to be who I am – a painter.”

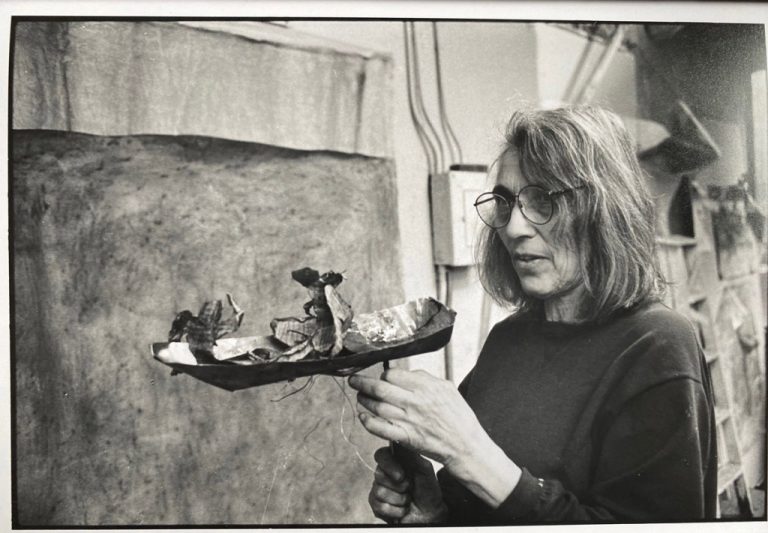

June Leaf, center, and her husband, photographer Robert Frank, left, in 2016.

Image via Taylor Hill, Getty Images

That was the era when Leaf met Robert Frank, a photographer and filmmaker who was already making a name for himself. They married in 1971. Frank then sent Leaf to find a home for them in Nova Scotia, and she found one in Mabou, where they lived throughout their careers. (They had two children, Andrea and Pablo, and remained married until Frank’s death in 2019.)

Her work has largely gone unrecognized, though she had an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 1978. In 2016, a modest exhibition of her paintings was held at the Whitney Museum in New York, one of the few major institutional shows she has had in recent years.

Photo: Dario Lasagni/Ortuzar Projects, New York

Much of Liv’s art is devoted to finding new ways to see the world, a project she translated into a group of sculptures that take the form of glasses. But while glasses are meant to clarify vision, Liv’s sculptures distort it, placing yellow cones or mirrors where lenses would normally be.

“I consider myself an inventor,” Leaf once said, “even though I’ve never actually invented anything, except maybe glasses.”