More than a decade ago, Dorita Sewell of Florida and her late mother, Doris, received a painting from a distant relative. It was an unsigned portrait of a fair-skinned woman with dark curly hair. The painting had been passed down through generations of family members, and they speculated that it belonged to an ancestor from the early 1800s. For the next decade, the mysterious painting sat wrapped in protective plastic in Sewell’s apartment until a little over a year ago, when she stumbled upon a lecture by journalist James Johnston, who was about to speak about self-taught Georgetown portraitist James Alexander Simpson.

“I thought, ‘Maybe he can tell me something about my paintings,'” Sewell told Allergic.

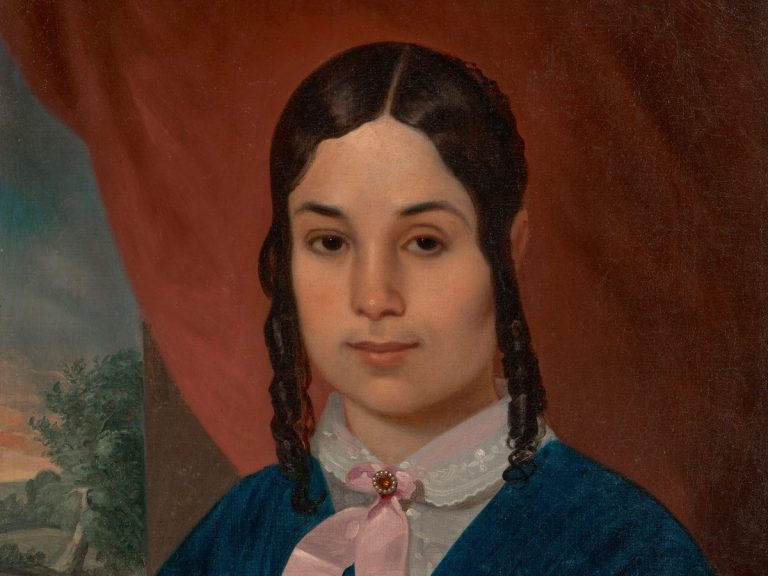

Now, years of unanswered questions and unproven theories have finally been put to rest as the work goes on public display for the first time today (June 26) at the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA). The BMA’s curator of American painting and sculpture says it is Simpson’s work. Virginia Anderson determined that the painting depicted Mary Ann Treat Cassel, a mixed-race woman who lived in the 19th century, based on the style, the subject’s clothing, and the conventions of portraiture at the time. Allergic She also compared the painting to Simpson’s portrait of Mrs. Henry Law Mudd and found striking similarities in composition and brushwork, as well as a portrait in the Smithsonian’s collection that was also created at a similar date to Sewell’s painting.

While formal individual portraits of African Americans were extremely rare during this period, this work is of unique historical significance as it is likely one of the first known commissioned portraits of an American born into slavery.

Johnston recently Washington postIt is suspected that Cassel’s mother, Henrietta Steptoe, likely purchased the painting as a wedding portrait. Born in 1779 at Stratford Plantation in Virginia, Steptoe spent the first third of her life enslaved by the Lee family until she was freed in 1803. She then moved to Georgetown, joined a community of free African Americans, and worked as a midwife and nurse. In 1807, she gave birth to a daughter, Mary Ann.

In 1839, Mary Ann married William Cassel, a black man from Baltimore and an active member of the American Colonization Society, an organization that sought to send free black Americans back to Africa to prevent their assimilation into white society. In 1850, the Cassels moved to a black American colony on the coast of Liberia, eventually establishing a permanent residence there, leaving Behind is a portrait of her and her sister Rebecca.

Johnston told Allergic“Her mother escaped slavery, her daughter was educated. She went to Africa. She taught in a school, ran a hospital, and that was only a generation away from slavery.”

Mary Ann died on February 15, 1871. After Rebecca died, she included a note in her 1877 will bequeathing a painting of her sister to her granddaughter, and from then on the work has been passed down the family tree to Sewell and her mother, who died in 2016.

“There are only five or six bequests in the will, so it’s clear this was one of her prized possessions,” Johnston said, thanking researchers Carlton Fletcher and Jack Farling for notifying him of the document as he was investigating the portrait’s provenance and history.

This work is not Simpson’s only painting of marginalized figures in American history. The artist also painted one of two known portraits of Yaro Mamut, a formerly enslaved African American Muslim man who lived in the same Georgetown neighborhood as Henrietta Steptoe. The work is currently on display in the Peabody Room of the Georgetown branch of the Washington Public Library.

Sewell told Allergic Now that the painting is on display, she plans to eventually visit the Baltimore Museum of Art.

“My mom and I spent a lot of time there. [at the museum]”, she recalls her mother’s love of sketching and how as a child she would “drag her mother” to the National Gallery to see the art on display.

“Now [at the BMA]“I’m excited about it,” Sewell said. “I think it’s awesome that we can all enjoy it and learn from it.”