The Guggenheim Rotunda is bathed in the glow of these familiar single-line phrases in all caps: “Taste the good, for the cruel will always be there,” “Money makes the taste,” and “I will think before I can’t think anymore.” These phrases, boldly typographic and deadpan, are unmistakably Jenny Holzer’s word art. Over a career spanning five decades, the artist has effectively trademarked the concept of language floating in space, aiming to disrupt our tendency to passively receive information. While her practice has evolved with changes in technology and society, her core concerns—language and power—have remained constant.

Holzer’s seamless integration of blunt statements about power into public settings reaches new heights in the Guggenheim Museum’s “Light Line.” The installation’s centerpiece is an LED light installation that stretches up the museum’s entire ramp, presenting a series of aphorisms about power dynamics, war, surveillance, and existential anxiety in a stock-ticker-like manner. In this extended reenactment of the 1989 installation, some phrases are recycled from Holzer’s “Truth” (1978–87) and “Incendiary Essays” (1979–82), while others are regenerated using artificial intelligence. Regardless, the authorship of the phrases is intentionally vague—a common thread for Holzer, whose artistic practice originally centered on anonymity. Such a major reenactment of one of Holzer’s most ambitious projects reminds us of her continued relevance: “Light Line” immerses viewers in a dizzying spectacle. As Holzer’s fame grew, so did the scale and complexity of her work.

Holzer began her career as an abstract painter, and during the rise of the fast-paced media culture of the late 1970s and early 1980s, she began to move away from the formal aspects of abstraction and toward incorporating text into her artwork. By strategically placing her text-based works in public spaces, she found that art could engage even those who were not actively seeking it, sparking thought and debate. Initially uninterested in exhibiting in galleries, Holzer gained attention for her “Truth” series (1977–79), which she began while a student in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s independent study program. Printed on white paper, these phrases—some Holzer invented, others appropriated, such as “Abuse of power is not surprising” and “Protect me from what I want”—were initially posted anonymously in Lower Manhattan. Later, they were printed on merchandise such as stickers, baseball caps, and T-shirts. While this series has a certain grim undertone, in her more provocative “Incendiary Essays” (1979-82), Holzer incorporated inflammatory statements from Mao Zedong, Vladimir Lenin, Adolf Hitler, and others into a unified essay format, each consisting of 100 words divided into 20 lines.

Holzer’s pioneering use of language as an artistic medium blurs the line between art and everyday communication. Whether she’s dabbling in advertising aesthetics or replicating the authoritative fonts, designs, and tone of a political message, her intention is to question and provoke rather than to parody. While there are clear similarities to contemporaries such as Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, and Louise Lawler, Holzer’s approach to language is not rooted in persuasion or confrontation. Instead, she employs mysterious, free-floating language—equally compelling, with the enchanting authority of anonymity—to maintain the ambiguity of meaning and undermine traditional systems of language.

In the 1980s, Holzer explored new ways of incorporating text into three-dimensional space. She adorned benches, plaques and sarcophagi with iconic aphorisms, all of which evoked authority and commemoration, allowing her expansive statements to exist in a specific context. In her “Life” series (1981), she presented short instructional texts on bronze plaques, conveying an unremarkable, institutionalized voice. Yet their content is surprising, revealing intimate thoughts about everyday life: breathing, sleeping, and relationships. Holzer’s now-iconic granite benches, which she began creating in 1986, are also included in the current exhibition, “Light.” It is this series that allows her to subtly intervene in the urban landscape, replacing impersonal signs with political or intimate messages, disrupting the norm of public memorialization.

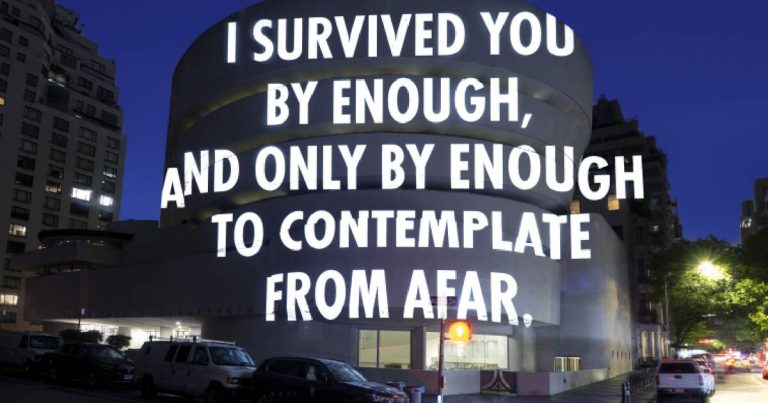

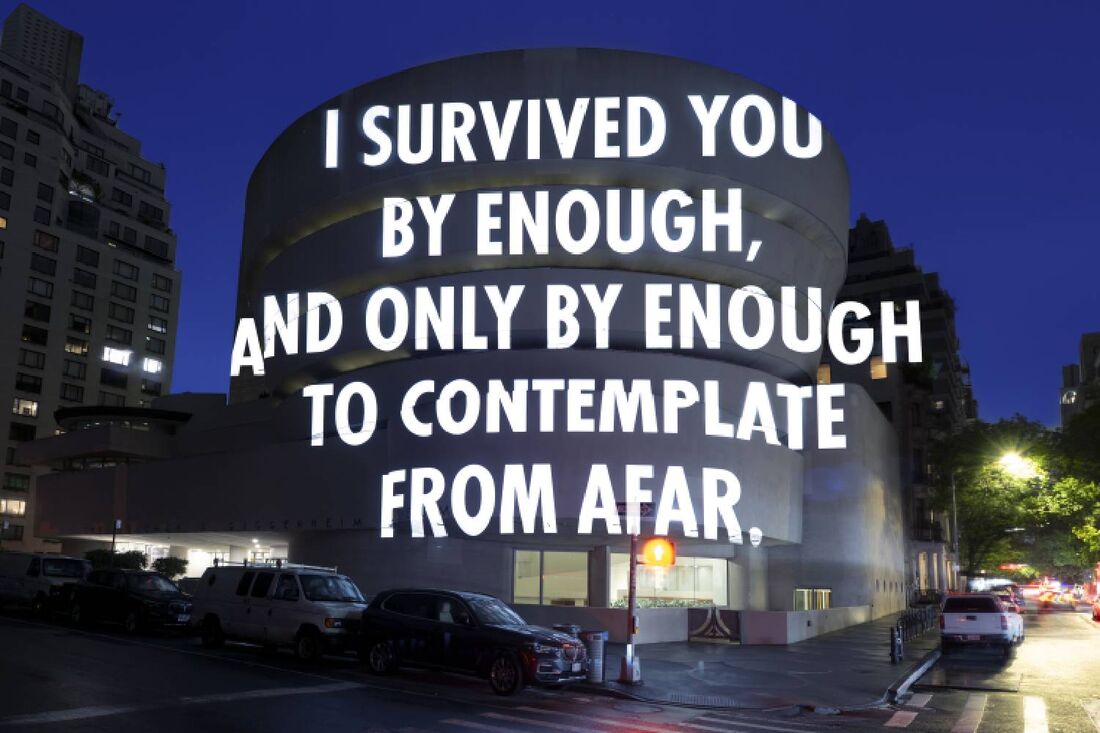

Holzer’s exploration of LED signs, with their new ability to display dynamic text, led to the Public Art Fund’s Spectacolor board project for Times Square, commissioned in 1982. Recognizing the signs’ potential to create immersive and site-specific experiences (unlike traditional paper posters, which had activist and DIY associations), she continued to use them to give text an unbiased sense of authority. Her 1989 installation at the Guggenheim Museum transformed half of the iconic spiral into an arcade. “Light Line” reinterpreted that installation, expanding it to encompass the entire six-story spiral and updating it with flashing and strobing color effects.

Holzer continues to explore the politics and patterns of modern information systems in the public sphere. In epic light projections, she began using the facades of monumental buildings around the world—from Rockefeller Center to Singapore City Hall—as canvases, projecting scrolling text that glides across the building’s surface before dissipating into the night sky. These nighttime light displays carry an undertone of institutional critique that resonates in her site-specific art. In 1990, Holzer made history as the first living female artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale. Her installation there, featuring multilingual text that flashed on LED signs, etched into marble benches, and carved into the pavilion’s marble floor, earned her the Golden Lion for Best National Pavilion. Holzer adapts her work to each context, allowing her to remain versatile even as her mode of expression remains consistent.

Holzer returned to painting in the new millennium. In her Redaction Paintings (2005–present), she creates silkscreen canvases based on declassified military documents and redacted government documents. This body of work, on view in the upper reaches of the Rays Rotunda, features infographics from government reports, books on artificial intelligence, and email correspondence between members of Congress transformed into large-scale paintings.

While the central section of “Light” subtly activates the entire ramp, the museum compartments remain mostly empty, recalling the blacked-out lines of her “Editorial Paintings.” However, beyond the obvious spiraling paths (such as stairwells or other less obvious corners), there are other artworks, including recent watercolors based on heavily redacted reports and documents on Russian influence on the 2016 US presidential election. Holzer once again surprises by subverting the traditional display procedures of museums and institutions, carefully reminding us to observe carefully and consciously ask questions even as her own dazzling light show captures our attention.