LOS ANGELES — Just over a hundred years ago, in 1912, Otto Dix painted “Self-Portrait with Carnations.” Two years later, the world in which this Renaissance-inspired work was created was no longer. World War I had begun, and the Europe of Hans Baldung Grien and Hans Holbein seemed unrecognizable. But Dix, the Nietzschean, knew better. Resentment and oppression were ever-present, fighting against the will to liberate. In 1914, they triumphed.

That year, the world changed irrevocably, with effects that still resonate today. Every year since, the war has been expected to get better. The war was expected to end, but it didn’t—it took four years, and Dix was haunted by nightmares throughout the war.

Imaginary Battle Lines: World War I and Global MediaCurrently on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, it is an elaborate overview of art and popular media related to World War I and a profound reflection on a war that has been neglected in American education despite its foundational role in creating our modern world.

In times like these, art can get bogged down. In their 1920 essay “The Art Scoundrel,” George Grosz and John Heartfield, who were in the heat of Berlin Dada at the time, attacked Oskar Kokoschka for advocating for the protection of cultural heritage during the turmoil that followed the Dresden Kapp-Luthwitz uprising. “We are glad to see bullets fly into galleries and palaces, into Rubens’ masterpieces, rather than into the homes of the poor in the working class quarters,” Grosz and Heartfield wrote. The logic is hard to argue with.

But what else can nourish the spirit when the world and ourselves are left with only the most desolate landscapes? In 1920, the Berlin Dadaists might not have said the answer was art, but they were making it. Dix, more of an aesthetic than his peers, might have acknowledged the existence of art, though he might also have scoffed at the idea—or agreed with a caveat: if it was to work, nourishment had to be disgusting.

In all the exaggerated images and film clips There is a small untitled painting by Dix in the exhibition, from the museum’s Rifkind Center for the Study of German Expressionism. I hadn’t seen it in several years, because I was writing my thesis on Dix and had studied it privately in the Rifkind Center’s library, and most people have never seen it, because it is rarely exhibited.

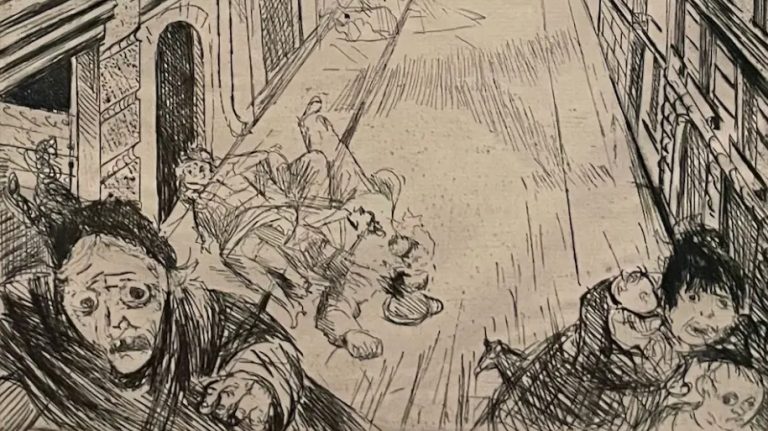

Painted during the Armistice of 1918, the surface of this painting is covered with grimaces, outlined in pencil over grey and black watercolor. Intersecting lines repeat several crosses and suggest barbed wire. There is nothing to suggest this is a political statement on the war—which is rarely the case with Dix’s work. Instead, it evokes a half-remembered dream, a desolate landscape that the artist survived.

To someone who hasn’t written a dissertation on Dix, his art might not seem very relevant on the surface. But what he so deftly conveys is that fear and trauma are felt, not thought about, and that art about these experiences can do nothing but didactic history when trying to make sense of things.

This is far from Dix’s scariest or most horrific painting – his “War” triptych, painted in Dresden in 1929-32, was a hellish reprisal of Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, and his 1924 war etchings are full of nihilism and decay. But this breathless little painting, created when the war was still fresh in people’s minds, with its ghostly faces staring back at it, is particularly disorienting. It presents violence and terror from the inside out.

If the painting offers a glimpse into the unspeakable horrors Dix endured, the worldwide response to it makes it relevant again and again.

Imaginary Battle Lines: World War I and Global Media The exhibition is on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (5905 Wilshire Boulevard, Mid-Wilshire, Los Angeles) through July 7. The exhibition is curated by Timothy O. Benson, Robert Gore Rifkind Curator of German Expressionism at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.