I remember the first time I saw an ad for bananas; this is for Frozen 2it felt like the beginning of something and everything turned into advertising. I guess I ate that banana in 2019, and look how far we’ve come: This year’s blockbuster The Lego Movie is itself basically an ad for Lego and a biography of rapper Pharrell Williams film, he is also the creative director of Lego Louis Vuitton. Where does culture end and advertising begin? They don’t want you to know.

when a freezing Or when a Pharrell-esque talent emerges, brands will struggle to find a way to capitalize on the attention they attract. In the art world, crossover mostly occurs between artists and luxury fashion, as both fields attract wealthy clients. When these fashion collaborations began to take over the art world, around the time of the Banana ad, I was optimistic: fashion money would surely defeat the nefarious sources of wealth being harvested through the opaque art market. Artists and brands work together to make cool stuff, like Anna Uddenberg’s sculptures for Balenciaga and Tyler Mitchell’s photos of Ferragamo at the Uffizi Gallery.

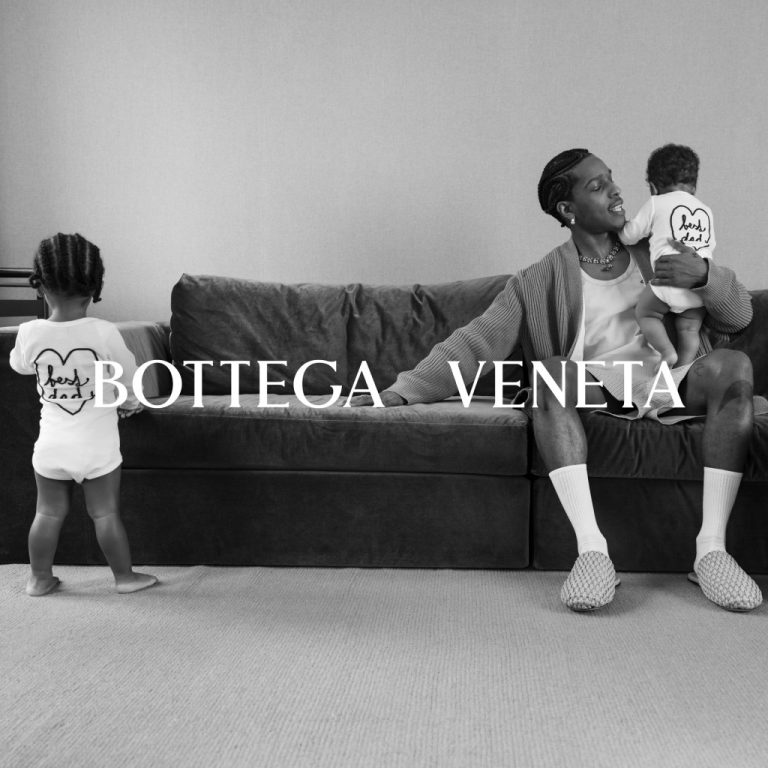

But then I started to feel like art and marketing were starting to merge into one. I felt this keenly this summer when Carrie Mae Weems launched her Bottega Veneta ad campaign. In one of the black-and-white photos, A$AP Rocky sits at a kitchen table, facing a mirror; the artist stands behind him, hands on his shoulders. The Bottega logo-covered image, which debuted on Father’s Day, is a refutation or remake of Weems’ iconic 1990 “Kitchen Table” collection.

Kelly Mae Weems: Untitled (Man Smoking)from the Kitchen Table Collection, 1990.

The collection has a kitchen table but also a message – one that feels hard to reconcile with ideas of luxury and Father’s Day. Over the course of 20 images and text, we see a black woman (Weems herself) become a mother and then watch that mother learn to be alone. The father of her child is out of the picture, and she sits at a kitchen table in a sparse room painted white, far from a plush kitchen table. She is poised and tenacious. In that ordinary room, Weems built a rich world. Over the course of the series, others join her at the table, acting out daily conversations and family dramas. It’s always the same shot—lights hanging overhead, door to the right—but the people in the photo change, as do the photos on the wall behind them (one of them shows Malcolm X). Her ever-evolving kitchen world is a tribute to the nameless worlds cultivated by countless women in countless kitchens.

It feels wrong to see a piece of art as powerful as this one turned into an advertisement. There are plenty of works of art that can be easily repackaged into pure style with little to no trade-offs. But this collaboration is harder to live up to the original—I don’t think that’s a dig at Weems’s involvement in something that many other artists have also been involved in. Quite the opposite: it’s a celebration of the power of the original series, which is definitely art, not just an aesthetic or personal brand.

We used to call it “selling out,” Back then, when it was mostly white people with generations of wealth who could label things, it seemed possible to be a creative who didn’t have to compromise on eating. But as Jay Caspian Kang said new yorker Last year, “people who grew up during or after the 2008 financial crisis… didn’t have much patience with Generation X, who were nostalgic for bands that ignored major label attention, or ad buster Or whatever. “

For weeks, “What do you think of the Carrie Mae Weems Bottega commercial?” was the question I asked at any dinner table I happened to sit at. The predictable defense involves not the image itself, but the idea that it’s good for the artist to get paid, and it’s good for the brand to support the art. Others added that artists might as well say “yes”: Brands are going to steal your idea anyway, so you might as well get something out of it.

To be fair: Apple’s 2004-08 iPod campaign copied Robert Longo’s iconic series of 1980s silhouettes, which swayed back and forth in movements that can only be described as “dance.” Longo later said in an interview that he was angry watt magazine, but in 2010 Bottega Veneta also approached him; he told watt They were essentially saying, “We don’t want to deceive you, we want to hire you.” He jumped at the chance to snap new photos of businessmen clearly in a state of ecstasy – this time wearing Bottega.

Production photos from the video for Charli XCX’s single “360,” 2024.

Photos of Aidan Zamiri

A more 2020s-style rip-off appears in Charli XCX’s “360” video, itself an ad for a Google product. One scene bears a striking resemblance to a photo of Deana Lawson. In a drab living room with mismatched furniture and low-quality light fixtures (but well-lit for the subject), a group of people face the camera, their body postures somewhere between candid lounging and dramatic poses. The midriff was exposed between the glamorous outfit. High heels embedded in the thick carpet. This dissonance makes the scene feel more realistic and stagey, a signature move of Lawson’s.

Throughout the 20th century, Photographers strive for respect as artists—to view the camera not just as a commercial or mechanical tool, but as an artistic tool. Alfred Stieglitz, with his illustrations, gallery 291 and his diary, Camera Notesinspired a generation in the 1910s to view photography as something as pictorial and expressive as painting and sculpture. In the 1970s, William Eggleston did the same thing with color photography, insisting that the medium’s appeal lay not just in advertising but in artwork.

It worked: art photography is so different from advertising that photographers are now conflating the two. Tyler Mitchell, Jurgen Teller and Roy Ettridge all had success

Playing ping pong between gallery and gloss. For Mitchell, it’s about celebrating Black joy and excellence in all its forms, from the glamorous to the everyday. Meanwhile, Ethridge was exhibiting everywhere in the 2010s, and his early work was seen as satirical commentary on advertising and editorial clichés. But soon his art and advertising became indistinguishable: Chanel Mackerel Bracelet (2013), 5th edition, showing a fish trapped in a luxury bracelet. It is in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art… and was part of an advertising campaign he photographed.

Complain, if you will, that the fusion of luxury advertising and contemporary art is selling out. Jay Caspian Kang is right; new yorker article, bemoaning the fact that “we’ve essentially given up on the ‘sell out’ part of the criticism, which assumes that nothing truly interesting or revolutionary can be found on a mass-market platform.” However, it’s hard to compare to mass-market It feels like how “revolutionary” the art world is today. Today, protecting art for art’s sake can make you an elitist gatekeeper.

This means that one could paradoxically argue that there is, in fact, a class politics at play when speaking to audiences outside of galleries and museums, because even if your audience cannot afford luxury goods, they may enjoy fantasizing about it, And more likely to see something extravagant. There are more ads in yellow cabs or magazines than in museums. They don’t have to pay an admission fee, and, as a bonus, they don’t feel like they’re not getting it if they don’t have an art history degree (that’s okay, there’s probably not much to gain). What’s more, advertising may actually have the power to influence the cultural imagination and change what we want: expresswhich is very popular.

The music industry is less susceptible to elitism Than art solves the problem of advertising. Proponents of collaboration believe that if musicians want to survive financially, they should adapt well to the changing media landscape, as Tina Turner and David Bowie did in a 1987 Pepsi ad That way, they might even be able to infiltrate the mainstream with radical ideas. Twenty years later, few musicians are making money from actual music. It’s all tours, commercials and sneaker collaborations. Will visual artists be next?

In January of this year, Cindy Sherman, who has long resisted commercial works, released a Marc Jacobs advertising campaign. Like Weems, she used her signature move in Taylor’s photos – dressing up as someone else for the camera. Sherman’s groundbreaking work in the late 1970s had an impact on the “Picture Generation”, a group of artists who responded to how commercialized the utopian counterculture of the time was, producing photographs that betrayed the idea that everyone was a critic and The consumer media landscape. Making the ad, then, goes some way to proving Sherman’s own point about the image. Unlike Weems, the sincere message is not replaced by the product. Instead, Marc Jacobs is just another costume Sherman wears.

Debbie Harry in Gucci campaign, photographed by Nan Goldin.

Photo courtesy of Nan Goldin/Gucci

Last fall, Nan Goldin’s Gucci ad campaign featured blonde singer Debbie Harry sitting in the back seat of a vintage car, holding a Puppy and a beautiful bag. Like Goldin’s iconic work from the 1980s, this is a portrait of an artsy New Yorker, dressed up for a night out downtown. But take away the intimacy, spontaneity, lo-fi camerawork, resourcefulness and courage of Nan Goldin’s photographs, and what are you left with? Just an ordinary picture. Harry’s lighting is impeccable and the footage feels impersonal, like a still from a Hollywood remake of the stunning 2022 documentary about Golding’s life, All beautiful and bloody. The campaign proves that Golding’s signature is virtually inimitable, even by herself.

We should ask, does fashion support art or embrace art? A museum director recently mentioned to me that younger patrons are proving harder to attract because they are investing in their own wardrobes. In addition, now they can take artistic inspiration from fashion shows—paintings, sculptures, installations.

On the other hand, brands like Dior and Chanel seem to understand why a complete collapse won’t work, and so sponsor museum exhibitions, buy ads in art magazines and collaborate with artists. They support the ecosystems that create art Artinstead of eating everything yourself and turning it into something else. Because without these ecosystems and their conversations, not only would the art be less good… there would be fewer opportunities to show off your gorgeous outfits at celebrations too!

What’s really worth defending about the collapse of the art and luxury world is not exclusivity or art-world insider baseball. This is a field set up for experimentation and adventure, for the weird and the useless, for art that can challenge, delight and surprise.