Art

Emily Steele

Isel Colquhoun, arbor1946. © Samaritans, Noise Abatement Society and Sister Perpetua Wing of St Anthony’s Hospital, Surrey (now part of Spire Healthcare). Courtesy of Dr. and Mrs. Richard Shillito.

One hundred years after the Surrealist movement began, its themes still have strong relevance. This year, a major traveling exhibition led by the Center Pompidou captures Surrealism’s enduring and more popular themes, such as dreams and psychoanalysis. Other exhibitions focus on the individual works of the movement’s biggest names, such as “Man Ray Liberating Photography,” at the Elysée Photo Gallery in Lausanne, Switzerland; or “Dalí: Subversion and Devotion,” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. However, there were many lesser-known themes in the Surrealists’ work, such as family, and many of the works exploring this theme were created by female artists.

The less discussed subject of family and intergenerational trauma takes center stage in a new exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute and Hepworth Wakefield in the UK. Some of the featured artists explore the role of parents in World War II, while others explore the oppression of women in traditional families. Ultimately, Surrealism provided a way for female artists to explore the complexities and entanglements of the family unit and broader political and social structures. The founder of Surrealism, André Breton, saw the family as one of several oppressive structures that needed to be dismantled, writing in his 1924 manifesto of the movement: “Everything remains to be done, by all means. It has to be worth trying in order to pay the price.” The idea of family, country, religion is wasted. ”

Leonora Carrington, On board the ship (Edward James)1954. © Estate of Leonora Carrington/ARS New York and DACS London. Provided by YDC

Jean Arp, The scenery is still a woman1962. Photography: Rüdiger Lubricht, Worpswede. Courtesy of Hepworth Wakefield

Surrealism was an innovative, unorthodox movement that allowed artists to break away from many of the restrictive ideals that found shape and form in traditional homes. For many women, Surrealism enabled a powerful reckoning with the past and reestablished the value of female life in the postwar world, extending far beyond the confines of the home. These artists, especially those who came to prominence after World War II, saw the family unit used as a propaganda tool for Nazi recruitment and a structure ruthlessly dismantled for those oppressed by the regime.

The exhibition “Traumatic Surreality”, on view at the Henry Moore Institute through March 16, 2025, focuses on German, Swiss, Austrian and Luxembourg women artists of the postwar generation, such as Renate Bertlmann , Pipirotti Rist and Ursula. Inspired by co-curator Patricia Allmer’s 2022 book of the same name, the exhibition explores how the shadow of World War II and the first wave of Surrealism in the 1920s and 1930s shaped Later artists. Some of these artists could see their own families’ experiences of war and the pride, fear or shame that came with it. As such, their works are filled with nightmarish and escapist references: metal cages abound, nestled among spikes protruding proudly from chests and masses of animal fur and feathers.

Merette Oppenheim, squirrel/ squirrel, 1969 © DACS 2024. Courtesy of LEVY Gallery, Berlin/Hamburg.

Renate Bateman, vote1985. © Renate Bertlmann / Bildrecht Vienna / DACS 2024.

“I think all works of art play an important role in different ways in documenting the impact of personal, familial and historical trauma,” Olmer said. “Surrealism’s interest in the unconscious, dreams and spiritual life made it ideal for documenting these intergenerational traumas, which were often only perceived indirectly and certainly experienced at a distance by postwar generations of artists.”

One of the early adopters of Surrealism, Méret Oppenheim takes center stage in the exhibition. Her work was influenced by her own family’s experiences during World War II. A German-born Jewish artist who fled to Switzerland with her family when the conflict broke out, she is said to have suffered a depression and creative block that lasted more than a decade after the war. The artist destroyed most of the works she produced during this period. This is not the first time state violence has affected her family. Shortly after her birth, her father was drafted into the Army to fight in World War I, and she moved with her mother to Switzerland to live with her grandparents.

Her whimsical sculptures have a sinister edge that reflects her own experience of family displacement and oppression during the war. Many of Oppenheim’s works are riddled with contradictions, highlighting the hypocrisy of postwar society as it attempted to reorganize itself in the years that followed. she squirrel (1969), located at the entrance to the exhibition, is a miniature work consisting of a beer glass and an upright, furry tail. The cruelty of this soft, tactile object is obvious: it has been hacked away from the squirrel’s body. Both the mug and the squirrel are “spoiled” to some extent, perhaps revealing Oppenheim’s feelings about the postwar family unit and wider social structures.

Birgit Jurgensen, Untitled(dog)/ Untitled (dog)1972 © Birgit Jürgenssen, Birgit Jürgenssen Estate / Bildrecht Vienna, 2024 / DACS 2024. Photography: Simon Veres. Courtesy Hubert Winter Gallery.

Birgit Jürgenssen was born in 1949, and it was not until later in life that she discovered her family’s complicity with the Nazi regime. Her parents discouraged art-making, and her feminist, avant-garde work dealt with her own family history and a broader critique of the fascist regime. In the decades after the war, her work reflected the repressive legacy of Hitler’s Europe, acknowledging that secret support and its associated beliefs remained intertwined with the collective consciousness.

Jürgenssen often places household objects in combinations with disturbing effects. exist seize happiness (1982), in which she used cages and offensive gear, all painted gold; Untitled (dog) (1972) is a small sculpture showing the soft entrails of a ceramic hound, as if its dark inner world were falling from its neat outer form. at the same time, Untitled (hint) (1967) shows a mass of soft textiles in the shape of a intestine, tightly packed into a bell jar. Her work explores the long-term impact of fascist ideology through the roles and constraints of Austrian women within and outside the home. In Jurgensen’s work, the domestic sphere of the family is tainted.

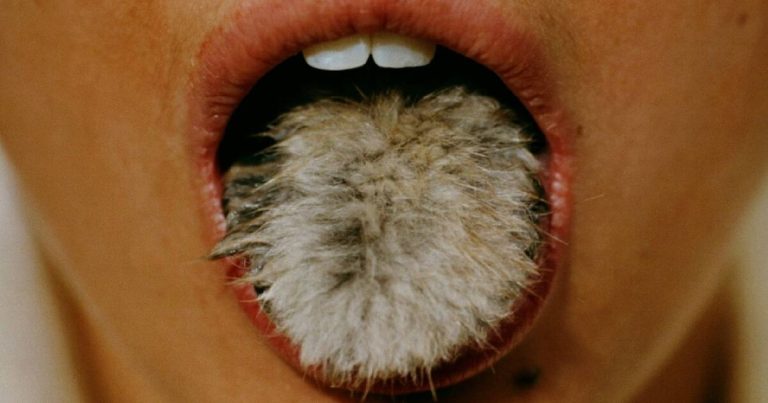

Likewise, filmmaker and artist Bady Minck’s family fought in the Resistance during World War II, 20 years before she was born. Her work continues this activism, using surrealism as a tool to resist fascist tendencies in culture through a feminist lens. She is one of the most contemporary artists in the exhibition, with her 2005 stop-motion animation Beauty is a beast Depicting behavior covered in fur, it is both creepy and seductive. The most famous shot in the work is of a protruding tongue covered in gray fuzz. The idea of perversion is at the heart of this work, which subverts the sexualization of women and challenges the strict gender divisions of Nazi ideology.

Buddy Mink, still from Beauty is a beast / Beauty is a beast 2005 © Buddy Mink. Courtesy of the Henry Moore Institute.

The Surrealists’ use of landscape in the Hepworth Wakefield exhibition mesmerizes the claustrophobic and sometimes malevolent undercurrents of domestic structures. Edith Rimington genealogy (1938) is a combination of montage and painting that contrasts a huge, heavy chain with the free sea around it. A snake crawled out from under the metal structure. The work is ambiguous, with the chain offering two possible readings of family: an unbreakable and solid structure that links one generation to the next, or a restrictive and oppressive one that demands conformity and obedience Forms of sex – especially female conformity and submission. The snake, which may be overlooked at first glance, is a symbol of the origins of the Christian family in the Garden of Eden and a poisonous, destructive force.

Also includes Maria Berrío’s Solstagia (2024). Her work focuses on displaced or broken families, often featuring women and young people. She was initially inspired to create the pieces following headlines about the Trump administration separating mothers and children at the U.S.-Mexico border. Here, the concept of home is central, as the work’s heroine finds her land alienated by a change in environment. The piece depicts a woman walking through a post-apocalyptic landscape, mentally broken, without her family and completely alone in a strange place.

maria berio, open geometry2022. © Maria Berio. Photography: Bruce M White. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro.

Of course, as the gallery looks back on one hundred years of Surrealism, we can see the impact that generations of artists themselves had on subsequent generations. There was a sense of family-like development in this generation of Surrealists, as ideas developed and exchanged over decades. “The intergenerational response among the artists in the exhibition shows the correspondence and resonance and ongoing dialogue between their works,” Olmer said. “The first generation developed Surrealist procedures and techniques that later artists could use to process their own traumatic experiences.”