Until the 1960s, the term computer Represents a worker (usually female) entering calculation results into a mainframe. The exhibition “Radical Software: Women, Art and Computing 1960-1991,” currently at MUDAM in Luxembourg and traveling to the Kunsthalle in Vienna, reveals the history of this gendered labor while also highlighting the female artists who experimented with or “thought” these machines . Looking at computers from a broad perspective in art history, it includes artists who use computers as tools and subjects, as well as those who simply “work computationally”.

The exhibition is divided roughly chronologically into five thematic sections. “Zeros and Ones” showcases early experiments in computing, primarily in the form of wall works, but also including kinetic sculptures by Liliane Lijn man is naked (1965), a fragile work from her “Poetry Machine” (1962-68) series, rarely seen in action. In the “Hardware” section, paintings by Ulla Wiggen and Deborah Remington evoke the mystery of the various technologies hidden behind their shiny exteriors, while “Software” Back to weaving, as the origins of “software” that defines computational output. “Home Computing” traces the availability of computers back to the artists who produced screen-based works through novel procedures. Finally, “I’d Rather Be a Robot Than a Goddess,” which takes its name from Donna Haraway’s 1985 “Robot Manifesto,” explores the computer’s influence on the (female) body through photomontages such as Valie Export and Analívia The impact of Cordeiro’s algorithm orchestration.

The show is organized around a technology rather than a genre, movement or medium, which results in unexpected and captivating content. Computational rendering by Isa Genzken ellipsoid (1977), for example, is shown alongside the sculptures it produced. The pairing highlights her ambition to make sculptures that she calls “mathematically correct”. elsewhere, house of dust (1967) is a computer-generated poem by Fluxus artist Alison Knowles, displayed on a vintage printer alongside a poem by Katalin Ladik Genesis 01-11 (1975), includes fascinating sonic explanations of various rapidly obsolete circuit boards.

Charlotte Johnson: Untitled (detail), 1981-85.

Courtesy of the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

Some of these early experiments revealed uncertainty about the status of “art objects.” Beryl Korot – Co-founder of the magazine radical softwarefrom which the title of this exhibition comes – display Text and comments (1976-77) as sketches, woven textiles and videos, and documentation of process. It was unclear where the artwork ended and the idea began, a move consistent with the Conceptual Art movement of the time.

The exhibition positions the emergence of computing as a process that eliminated any separation between fine art and craft. This rupture is welcome, as women have historically been excluded from the former category. This argument is most clearly articulated in the exhibition’s connections between computation and weaving: digital artist Charlotte Johannesson’s works are presented in sculptures in the form of weavings, digital paintings and digital images On the impressive LCD screen in the garden, he claimed that the screen’s pixels corresponded to the warp and weft of the loom.

But the exhibition here misses an opportunity to tell the broader history of the relationship between weaving and computing, particularly overlooking the efforts of Aboriginal women. There are no indigenous weavers in the exhibition, nor is there any mention in the exhibition of the women weavers who produced Intel microchips on the Navajo reservation, a story at least not seen since Marilou Schultz’s appearance at Documenta 14 in 2017. has been circulating in the art world.

Samia Halabi: bird dog 61987.

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut/Hamburg

Computing is infrastructure-intensive, and Radical Software traces how artists use computing in ways defined by limited access to these technologies. The exhibition claims to have a global perspective, but ultimately it doesn’t cut it: there are more artists named Barbara here than from the Southern Hemisphere.

The brochure and exhibition catalog include a timeline tracing women’s contributions to computing history. It covers the first use of the word “computer” in 1613 to the public use of the Internet in 1991. It blends iconic moments from figures like Ada Lovelace, NACA Computers, ENIAC 6 and Grace Hopper with women’s history and focuses on artists in the digital realm. In doing so, the exhibition connects its artists with women who worked in the military-industrial complex: the world’s first modern computer, ENIAC, was invented to calculate ballistic missile trajectories (programmed by six young women), while Grace Ho Grace Hopper is a naval officer. Any computer program the U.S. government launched during the Cold War was inseparable from its military efforts.

The exhibition revitalizes the stories of the women who developed deadly technologies whose stories deserve closer examination, as well as those who worked so hard to build a more equal world. The question is whether this shared narrative serves these artists, whose experiments with machines are described in exhibition materials as containing a “history of abuse.” There is no need to go to Girl Boss Ballistics.

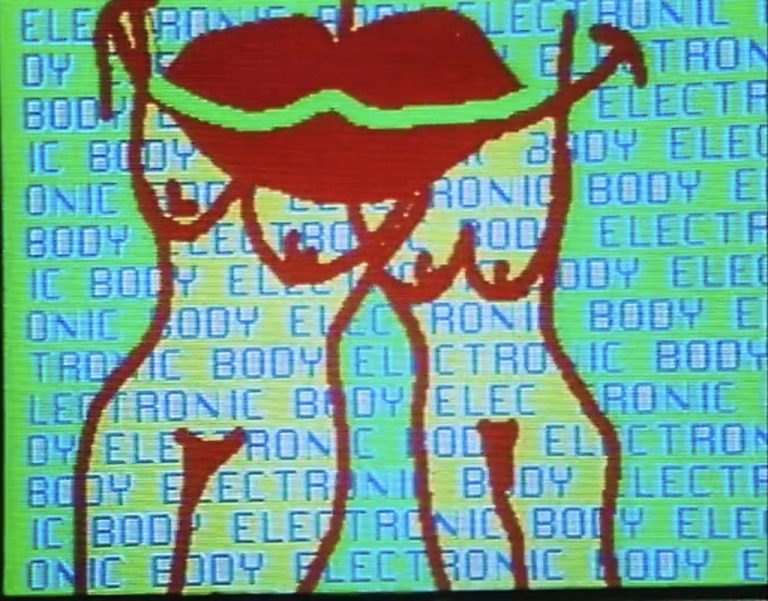

Darla Birnbaum: Popular Music Video: Kojak/Wang1980.

© Darla Birnbaum. Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Its potential is maximized when the exhibition showcases the artist’s brushes experimenting with the new toolbox. Barbara T. Smith external opportunities (1975) combined the best of programming with conceptual performance using 3,000 computer-generated “snowflakes” (which she threw out the window of her Las Vegas hotel room). Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s research on Ada Lovelace is expressed in the computer language ADA, proving a heartfelt biography in code. Samia Halaby’s dynamic paintings and soundscapes are a true complement to the BASIC and C coding languages she learned for her field of abstract painting.

“Radical Software” offers compelling new interpretations of art history through the means of computational technology. But when we are grappling with the impact of 20th-century technological developments on every field, whether social, artistic or military, inserting artists alongside engineers dedicated to military purposes is a betrayal of utopian thinking that Utopian ideas are omnipresent in the best works in the exhibition. Radical Software demonstrates that there is still much work to be done to properly recognize the female computer development workforce, as problematic pioneers and experimental abusers.