Emma Coyle has spent more than twenty years committed to a very specific conversation—one that starts with American Pop Art but doesn’t stay there. Originally from Ireland and now based in London since 2006, Coyle has built a career by pulling threads from the bold, media-driven images of the 1960s and threading them through her own lens. Her work doesn’t mimic—it responds. In 2022, her solo show The Best Revenge at Helwaser Gallery in New York found wide attention, landing at number 12 on GalleriesNow’s roundup of the “30 most popular exhibitions on now.” She’s represented by that same gallery today. But she’s not repeating her hits. Coyle stays in motion, pushing color, shape, and placement into unfamiliar territory.

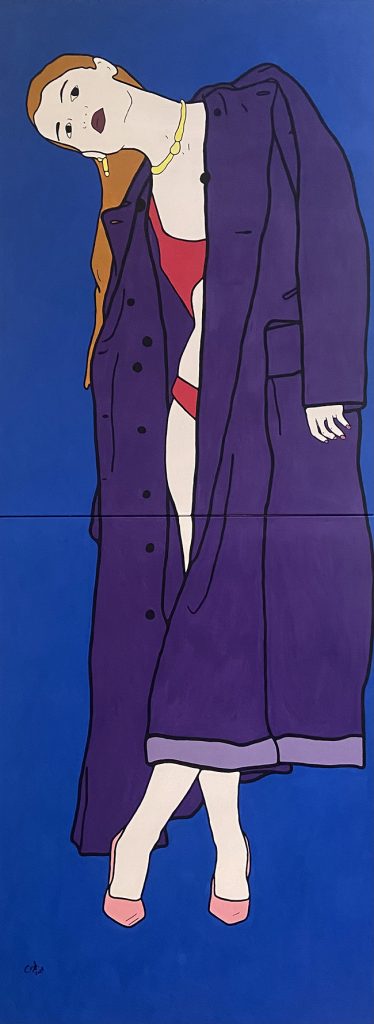

‘25.01’ (2025)

At 96 inches tall, 25.01 is the largest painting Coyle has completed to date. It’s not part of a series, and that’s intentional. She doesn’t want to fall into rhythm. This piece stands on its own, both in scale and approach. The central figure is off-centered, creating a deliberate imbalance. That sense of unease is the point—it keeps the eye searching.

Coyle’s roots in Pop Art are visible here: the color, the contour, the nod to commercial imagery. But she distances herself from nostalgia. Her aim isn’t to rehash the past. Instead, she uses those influences as a jumping-off point, layering in years of her own progress and technique. She sources images from contemporary advertising—ads that catch her attention not for their message but for their form. It’s not about consumerism, it’s about the visual mechanics of how people are sold to.

Line work, color palette, and scale all shift from painting to painting. She avoids formula. 25.01 hits hard not because it copies a Pop Art playbook, but because it wrestles with it—keeping some parts, discarding others, and adding something unmistakably hers.

‘The Slice’ and ‘Big Mouth’ (2025)

Coyle started the year with The Slice, a 48 x 60-inch acrylic painting that, like 25.01, features a purposely off-centered figure. This isn’t a quirk—it’s a decision that injects motion into a still image. There’s a quiet narrative embedded in the piece, but it doesn’t explain itself. It invites a second look.

Shortly after came Big Mouth, the same size but reversed in orientation—60 x 48 inches. These two paintings, she says, mirror each other in spirit. Both hold the energy of youth, and both are loud in their own way. But again, not loud like Pop Art once was—loud like something trying to say something new in a room full of echoes.

The brushwork and layout show Coyle’s interest in tension. Lines aren’t always neat. Colors push against each other. The figures, often drawn from fashion or beauty ads, are stripped of context and reworked into something else entirely. By removing the ad’s original intent, Coyle builds her own language out of its pieces.

Pushing Forward

Emma Coyle is careful not to repeat herself. That’s a through-line in how she talks about her work. She’s conscious of the traps: the temptation to revisit old images, the ease of letting one successful idea shape too many canvases. Instead, she continues pulling material from new places—recent media, fresh layouts, unfamiliar compositions. It’s always moving.

Her color palette evolves too. The brash tones of early Pop influence still show up, but they’re countered with quieter hues, controlled gradients, or unexpected cuts of negative space. She doesn’t aim for nostalgia, and she avoids irony. Her paintings are serious in how they deal with visual language—playful only in their reassembly.

What remains consistent is the impact. These works are big, not just in size, but in visual presence. They demand to be seen from a distance and explored up close. She’s still experimenting—with line, form, size—but it’s not chaotic. There’s method in the way her paintings hold space.

Final Thoughts

Emma Coyle isn’t standing still. Her art might owe something to the 1960s, but it lives in the now. With every painting, she’s threading her influences through a new frame, one that reflects the cluttered, fast-moving world we live in—but does it with precision, purpose, and quiet force. There’s a rhythm to her work, but no repetition. And that’s what keeps it interesting.