Kerstin Roolfs doesn’t make art that sits quietly in the background. Her work has weight—both in subject and scale. A German-American painter now based in the Bronx, Roolfs explores themes that many shy away from: physical deformity, mythology, sexuality, politics, and identity. Originally from Germany, she studied fine art in Berlin before moving to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in 1994, at a time when that part of New York was raw and humming with creative energy. She’s lived in the Bronx since 2016, and her art has traveled further than she has—shown in solo and group exhibitions across the U.S., Canada, Russia, and Europe, with museum exhibitions in Germany. She is currently represented by Twelvechairs Gallery (https://twelvechairsgallery.com/).

Her paintings are large, oil-based, and unapologetically direct. The themes aren’t always easy, but they’re layered with curiosity, boldness, and a raw sense of inquiry. If you stand in front of one long enough, you start to feel that it’s not just looking back at you—it’s trying to ask something.

One of her most ambitious projects is the Global Beings series. The first painting in this set—Global Beings 1#6—is nearly eight feet tall and wide, an oil on canvas that takes up a wall and demands attention. The inspiration came from a surprising place: the Charité medical museum in Berlin, which houses a collection of pathological specimens. Among them were preserved remains of deformed babies—once referred to as “children of wonder.” Roolfs connects their presence to ancient mythologies, particularly Greek stories where these unusual forms were seen as omens or sacred beings.

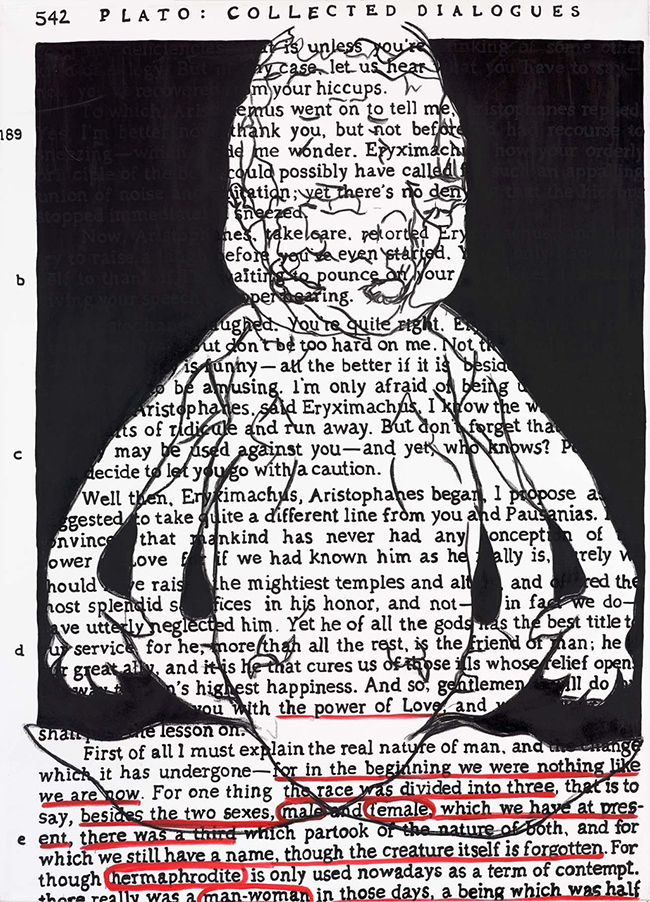

But this isn’t a work of horror or spectacle. The painting reaches further, pulling in ideas from Plato’s Symposium, especially the part where Aristophanes speaks about androgynes—those early humans who were both male and female, later split apart by the gods. Roolfs blends this philosophy into her painting. The beings she depicts are gender-fluid forms, tumbling and twisting across the canvas, interacting with handwritten excerpts from Aristophanes’ monologue. There’s a deep tension in these works: anatomical strangeness meets philosophical beauty. The beings don’t just exist; they search, cartwheel, and circle the text, almost like they’re trying to break through the canvas and speak.

Another work, Faces 2017, brings the viewer into a different headspace. Smaller than Global Beings but still substantial at 44 by 56 inches, the painting was made using the Surrealist technique of automatic drawing. That means there was no plan. No sketch. Just brush to canvas, allowing subconscious shapes and forms to emerge without censorship. The result is a field of androgynous heads and torsos—icons Roolfs says began appearing in her work soon after she moved to New York in the mid-90s.

These faceless figures aren’t haunted—they’re familiar. They reappear when she lets go of control, like symbols rising up from deep memory. For Roolfs, they’re something of a default visual language. She doesn’t force them; they just show up when she paints without intention. That makes Faces 2017 feel less like a statement and more like a confession.

Then there’s Women 2000, a 70 x 60 inch oil painting that closes out her long-running “Sister” series, which she began in the late 1990s. Unlike Faces 2017, this painting was carefully planned. Roolfs started with a small collage. From there, she made an ink drawing. Then she scaled that up into the large final painting. The layers of planning mirror the complexity of the subject matter—female identity, shared history, and emotional lineage.

Though her process varies—from automatic drawing to meticulously composed structures—what ties Roolfs’ work together is the way she uses painting to ask difficult questions. Her subjects often exist in the in-between: between genders, between cultures, between body and myth. There’s always movement in the work, whether it’s in the literal way figures are drawn or the emotional shifts they provoke.

Roolfs isn’t chasing beauty or decoration. She’s interested in how we process difference—how we look at bodies that don’t conform, how we understand sexuality beyond binaries, how we carry stories from ancient texts into today’s chaotic world. Her work holds those contradictions in place and invites you to look at them, to sit with them, and maybe to see something of yourself reflected back.

Her studio may be tucked in the Bronx, but her canvases stretch across continents and centuries. She paints like someone with questions to answer—and the time to ask them properly.