Roberto Chavez, an important figure in the history of Latino art in the United States whose work influenced subsequent generations of artists, died of natural causes on December 17 in Arivaca, Arizona. He is 92 years old. The artist’s daughter, Sonna Chavez, confirmed the news in an email.

Chavez was part of a generation of Mexican-American artists working in Los Angeles starting in the early 1950s, when they influenced the Chicano art movement. The group, which included Chavez and five other artists, was part of the UCLA Chicano Studies Center and the Autry Museum’s major 2011 exhibition “Art Along the Hyphen: A Generation of Mexican Americans.” ” theme, the exhibition was part of the first art exhibition. The Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time Initiative looked at Los Angeles art in the postwar era that year.

“In such an artistic atmosphere, [these] Mexican-American artists incorporated aesthetic and cultural influences into an artistic complex that not only defined them but also contributed to the flourishing of the Chicano art movement in the late 1960s and 1970s,” “Art Along the Mexican” Co-curator Terezita Romo Hyphen,” writes in the accompanying catalogue, Rasicano. “Yet most Mexican-American artists have been virtually erased from the mainstream art canon, absent from public art institutions, and missing from art school curricula.”

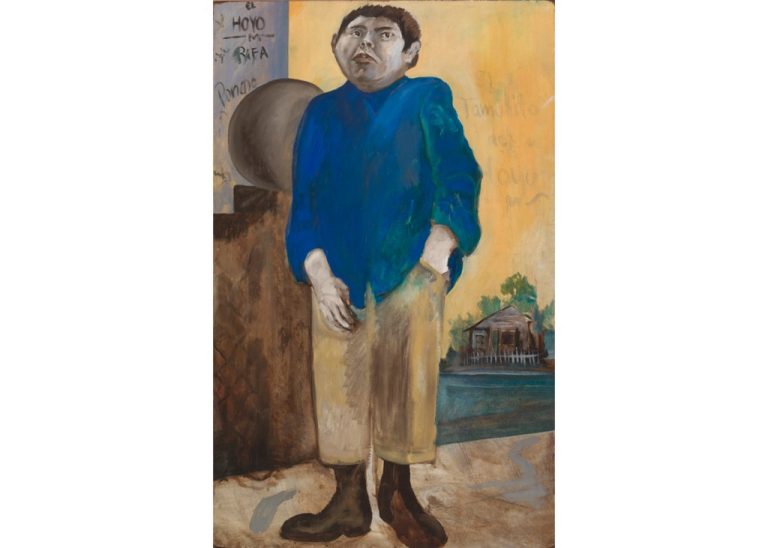

His 1959 painting, tamarito del hoyowas featured on the cover of “Our America: Latino Presence in American Art,” a groundbreaking 2013 exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. The canvas shows a man wearing a blue shirt and yellow pants standing in front of a graffiti wall. A small house with a white picket fence is seen in the distance.

“Tamarito, I never knew his real name; Absorbent cotton “Coming from ‘El Hoyo,’ it’s just blocks west and north of where I hang out,” Chavez once told Romo about the painting. “In high school, I realized that my contemporaries and our environment were the things I most wanted to depict in my photos and stories.”

E. Carmen Ramos, curator of the Smithsonian exhibition, wrote: tamarito del hoyo “This is Chavez’s tribute to the often invisible residents of Los Angeles’ many Mexican communities.”

In addition to paintings depicting Mexican-Americans and Chicanos in unknown parts of Los Angeles, Chavez also created several murals around the city, including one at the Estrada Court Public House in Boyle Heights A famous mural location in the area. The most famous—and most controversial—is The Road to Knowledge and the False University (1974-75), who painted this painting for the exterior of the auditorium at East Los Angeles College, where he was the founding chair of the Department of Mexican American Studies. The mural, which measures 30 feet by 200 feet and is visible from nearby Highway 60, is a dense collection of images and imagery, from war tanks and military aircraft to a surrealist-style pyramid and a pile of Cubism canvas, to floating corpses and fish.

The mural’s title refers to its two main parts. The upper register visually translates the four obstacles to knowledge written about in Carlos Castaneda’s book: fear, clarity, strength and old age. The Teachings of Don Juan. The second half more directly denounces Chávez’s so-called “Chicano intellectuals,” showing Laputa’s representatives Gulliver’s Travels“A group of elites are there engaged in esoteric and mindless activities – Chávez’s ‘Fake University,'” Romo said.

The mural was the focus of the 2017 PST exhibition “¡Murales Rebeldes!: LA Chicana/Chicano Murals Under Siege,” which looked at murals in Los Angeles that were painted over or destroyed. In the exhibition catalogue, co-curator Jessica Hough writes that the campus newspaper was particularly critical of the mural, providing “evidence of factions within the Chicana/o community at the time, and it is disappointing that the mural was not used more easily The identification of the Chicana/o image, as well as a growing rift between ELAC faculty and administrators, all culminated in the mural’s whitewashing. “

Decades later, Chavez recalled: “I knew that not everyone would like the painting. But when I did it, I did it as part of an educational environment where the themes, themes, expressed in it would come across to people. questions in your mind.”

Roberto Chavez was born in Los Angeles in 1932 to parents who immigrated to Los Angeles from Mexico after the Mexican Revolution in the early 1920s. They settled in the Maravilla neighborhood of East Los Angeles. He showed a preference for artistic creation in painting and sculpture from an early age. “My first sculptures were repurposed objects—recycled materials into small toys,” Chavez told Romo in a 2010 oral history.

In high school, Chavez decided he wanted to be an artist after seeing a painting by Braque in the window of the May & Co. department store in downtown Los Angeles. This work attracted him, and he also saw the works of other European masters such as Renoir. “It was as if they were alive in a way that I might have imagined but never seen,” he said in an oral history of the paintings. “I knew this was what I wanted to do. I wanted to create paintings that came to life.”

He first attended Los Angeles City College, where he studied commercial art. His studies were interrupted by military service during the Korean War from 1952 to 1954. After returning home, Chavez used GI Bill funds to transfer to the art department at UCLA, where he studied under William Brice and John Paul Jones. They celebrate purely abstract principles.

Yet Chavez chose a different path. His work is primarily figurative, although it incorporates abstract elements. Works he created while completing his BFA studies in 1959 include mask (1957), shows children with faces obscured by Cubist masks.

In his art, he wanted “to believe that the human figure is a reflection of myself and of life. Because I do not always know what I am painting, and revelation is as much a part of my painting as achievement,” Chavez said in his wrote his master’s thesis, which he also received from UCLA in 1961.

He soon began teaching extension courses at UCLA and ELAC. Around this time, he reconnected with three artists he had crossed paths with at UCLA: Eduardo Carrillo, Charles Garabedian, and Luis Luneta. The four galleries quickly established links with the Ceeje Gallery on La Cienega Avenue, which opened in 1962, and a year later the famous Ferus Gallery was just a few blocks down the street.

in 1962 art forum Reviewing the four-person exhibition dedicated to Chavez, Carrillo, Garabedian and Luneta, artist Arthur Secunda wrote: “[T]His team constitutes one of the most exciting, intense, and dynamic debuts of any art gallery opening here in recent memory. …I hope the boys on the street take note of this. “

Works exhibited by Chavez include Group Shoes (1962), a portrait of the four participating artists, all looking in different directions, seemingly avoiding eye contact with a lone brown boot resting on the edge of a yellow-cream table. (The painting’s title is an intentional pun on the phrase “group show.”) Chavez had his first solo exhibition at the Thayer later that year, and exhibited at the gallery until 1965.

In 1969, Chavez was hired as a full professor at ELAC, a joint appointment between the Department of Art and the Department of Mexican American Studies (later renamed the Department of Chicano Studies). His tenure directly overlapped with the heyday of Chicano movement political activity, and ELAC was the primary venue for this activity.

Although he was the founding chair of the Mexican American Studies Department and was commissioned to paint the mural for the campus, Chavez resigned in 1981, two years after the college painted his mural. He then moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where he lived for several years. his 1982 film executionan artistic response to the emotions Chavez felt after the mural was destroyed.

But that experience never diverted Chavez from his dedication to painting and his belief in its power. In an article published in 2011 titled “Why Paint?” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies“Art helps us feel comfortable with the experience and makes us feel how incredible it is to be human and live in this awe-inspiring and beautiful place,” Chavez wrote.

He added, “You could say I paint to discover what painting is.”