Within the pantheon of early 20th-century avant-gardes, Orphism—the subject of a comprehensive and wide-ranging survey by the Guggenheim Museum—is rare among isms because it remains relatively underexplored studied and misunderstood, at least in comparison to modernist homologisms such as Futurism, Vorticism, and Cubism. Cubism’s kaleidoscopic liberation of geometry from the etiquette of perspective inspired the Orphic push for “pure painting”—the liberation of pictorial form and color from the duties of representation—but, confusingly, The name of the movement is associated with literary allusions. It was coined by French poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire in 1912 and is reminiscent of the Greek mythological prophet and musician Orpheus. For Apollinaire, music provided a new mode for modern painting, distilled to its purest potential state, unencumbered by narrative exposition.

Although Orphism developed almost entirely in Paris, it involved artists of a wide range of origins and nationalities, and the Orphic painters’ focus on “pure” form and color was associated with non-objective painting from Germany to Italy to the United States. Other developments resonated. Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris, 1910-1930 goes a long way to contextualizing some of these similarities and intersections. Driven by an impressive array of loans, the exhibition illustrates the specific aesthetic achievements of Orphism and its amorphous taxonomy.

As the wall text points out, the painters most closely associated with Orphicism—Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Francis Picabia, and František Kupka— —Never adapted Apollinaire’s naming terminology to his own. They published no manifesto or book in its name, and the Delaunays used the term “simultaneity” to describe their work. But it is undeniable that formal ambition and visual impact unite some artists with different origins and different aesthetic trajectories, even if briefly.

View of “Harmony and Discord: Orphism in Paris, 1910-1930”.

Courtesy of the Guggenheim Museum

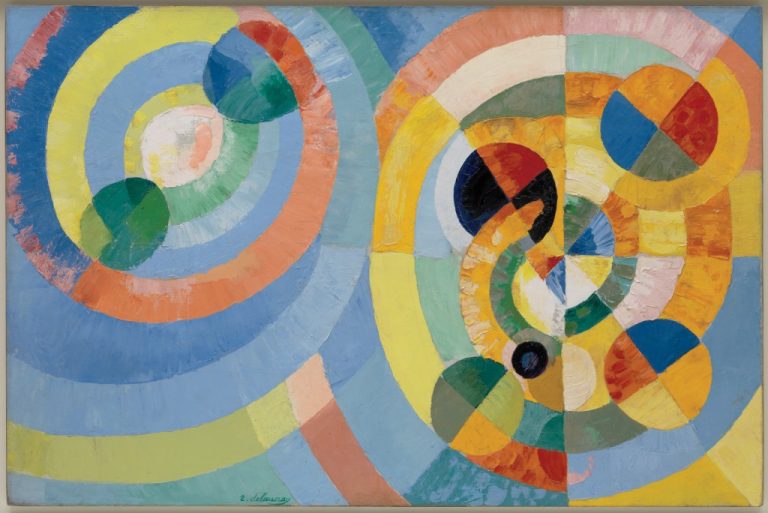

Tucked within the first loop of the Guggenheim ramp, the gallery combines the interconnected efforts of four core artists into incandescent reliefs, each in their most “Offician” form, via a large canvas each. Although traces of representation remain in some paintings – Robert Delaunay’s Pulsating Celestial Bodies Compare simultaneously: the sun and the moon (1913), for example, or the water rippling from the center of Kupka Localization of graphics themes (1912-13)—their imagery was primarily concerned with rhythm and texture. Empirical reality does not determine the hallucinatory swirls of color or the swirling of forms in the work, but arises from celestial inspiration or inner vision.

Wassily Kandinsky is just around the corner Improvisation 28 (1912) reminds viewers of the extent to which musical compositions influenced certain pictorial experiments over the years (while also documenting the explicit embrace of the work of Robert Delaunay by the Munich Blue Reiter group, centered around Kandinsky). Simultaneity in the music replaces polyphony with linear continuity – an effect that many of the works on display strive for. As art historian Nell Andrew writes in the exhibition catalogue, the inseparable union of music and dance proved influential on Orphic tendencies in painting (as in Orphic imagery Character and setting often prove to be indistinguishable).

The main ambitions of these painters were visual rather than intellectual. The Delaunay family paid close attention to the Post-Impressionist innovations of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, as well as the scientific color theory of French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. But the “contrast” through which they construct the image is not just visual or chromatic. Orpheus imagery provides an emotional response to the conditions of modern life in the metropolis and its increasingly cinematic, commercial, and mechanized sights and sounds.

Robert Delaunay: round table1930.

Christopher McKay, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Sonia Delaunay Electric prism (1913), whose title is a nod to the then relatively new advancements in electricity, emphasizes the distinctly urban tenor of Orphic painting in this regard. Poets like Apollinaire and the Futurists incorporated similar phenomena into their writing, both thematically and typographically, and Sonia did the same with Blaise, another modernist poet living in Paris at the time. · Cooperation with Sandlars. Accented by the stylized Eiffel Tower, her bright watercolor abstractions unfold alongside (and merge with) the poetry of Sandlars, whose “Transsiberia and the Prose of Petit John in France” hangs at the Guggenheim In a vertical exhibition in one of the coves – explore the transcontinental train journey during the first Russian Revolution in 1905.

The Eiffel Tower appears repeatedly in various paintings by Robert Delaunay as an icon of urban life, but it has become increasingly dematerialized. Even at their most abstract, his images refuse to give up the specter of figuration. This exhibition highlights with great flair the continuity of his work with that of other contemporaries. Delaunay’s Clouds Rouge Journey (1911-12), for example, bears no closer resemblance to a work painted in the same year by Fernand Léger, as can be seen in the rendering of Parisian rooftops in the Guggenheim Atrium. Giant prismatic clock with figures from Marc Chagall’s work Tribute to Apollinaire (1911-12) The Discs, also from the same period as Delaunay, rhyme unmistakably, just as Chagall’s depictions of the Eiffel Tower and Paris windows resonate with Robert Delaunay’s series on the same subject.

Robert Delaunay: red eiffel tower1911–12.

Mickey Waters, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

The show’s focus on personal and professional collaboration is illuminating. The Delaunay family’s influence on the painters Eduardo Viana and Amadeo de Souza-Cardozo – and the echoes of Portugal’s “native colors” in their own canvases – is particularly prominent in this regard . But as the exhibition progresses, some of the juxtapositions and the larger debate over the precise meaning and resonance of Orphism lose their impact. A poignant series of works diluted by a series of rather obscure inclusions. Given Marcel Duchamp’s relationship with Picabia, it makes sense that his early Cubist works would appear. In comparison, Jean Metzinger, Marsden Hartley, David Bomberg, Natalia Goncharova ) paintings and sculptures by Alexander Archipenko are represented in them by confusing, futuristic works by Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini The same is true. Vorticism, Rayonism, Cubism, and Futurism paintings all exhibit some common elements with Orphic abstraction, but the inclusion of works from different movements may confuse the uninitiated visitor as to the precise content of Orphicism , outline or consequences.

Regarding Archipenko’s works, Apollinaire declared that the artist “first pursues the purity of form” and obtains not only melody but also “harmony”. The same is true for all the artists in this exhibition. Yet in bringing so many tendencies under the umbrella of Orphism, the exhibition erases its actual edges as much as it seeks to define them. This may be intended to reflect the malleability of the name itself, but it also risks making Orphism all-encompassing – and therefore, nothing special.

Thomas Hart Benton: bubble1914–17.

©Thomas Hart Benton and Rita P. Benton Testamentary Trust/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS) VAGA, New York

The show’s extension of Orphic’s career into the 1930s resulted in a similar slack. Apart from a few sporadic reprisals by Delaunay and Kupka in interwar Europe, Orphism had largely faded away by 1914, although its innovations resonated in other experiments. American Synchronist painters Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell have received due recognition for their paintings produced between 1913 and 1917, while Thomas Hart Thomas Hart Benton’s paintings have also received due recognition. bubble (1914-17) reveals the allure of non-objective painting, even for the most unlikely artists of the mid-1910s. The striking electric blue of Mainie Jellett’s (1938) work certainly corresponds to nearby works. Meditations on Painting Created by Cubist Albert Gleizes (1942). But focusing on purely formal (and belated) resonances does little to illuminate a movement already loose and on the run. Despite these shortcomings, the exhibition brings together an impressive range of works and a fascinating look at the gathering of non-objective artists in Paris on the eve of the First World War. Even if the juxtaposition seems strained, the various individual paintings gain new light and tone in the exhibition’s vibrant polyphony.