Vicky Tsalamata lives and works in Athens, but her practice stretches far beyond borders—geographical, historical, and emotional. A Professor Emeritus in Printmaking at the Athens School of Fine Arts, she works in mixed media with precision and insight, using archival prints on Hahnemühle cotton paper to deliver sharp, at times sarcastic, reflections on the human condition. Tsalamata’s art doesn’t aim to soothe; it cuts. It questions. It demands that we consider how much, or how little, we matter in the grand machinery of history. Her ongoing series, La Comédie Humaine, nods to Balzac and, through that, to Dante, reminding us that the theater of life is as absurd as it is tragic. From social critique to imagined utopias, Tsalamata’s work walks the fine line between personal experience and collective memory, offering not answers but frames in which to look deeper.

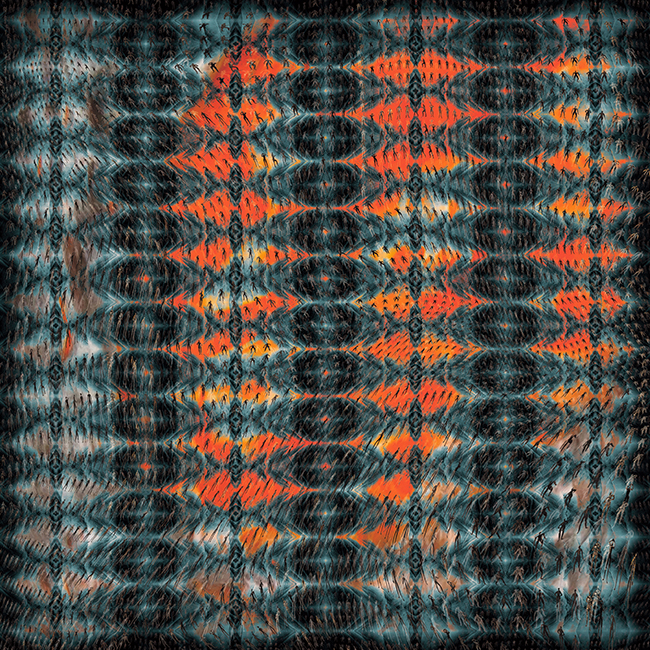

In her 2022 piece La Comédie Humaine, Give Me Your Hand, Tsalamata offers a stark vision of connection—or its absence. The title sounds like an invitation, but the work beneath it is laced with irony. We are offered a hand, yes, but the gesture is uncertain. Is it a plea, a trap, a farewell? Made with mixed media on fine art archival paper, the piece blends texture and tone in a way that feels both intimate and cold. The work doesn’t just reference Balzac’s massive literary attempt to catalog the spectrum of human behavior—it reenacts it visually. Figures seem isolated in a fragmented space, distant even in proximity. The layers of media echo the layers of human complexity and the systems that often reduce us to roles, data points, or nameless faces. Tsalamata points to how small we often are in relation to the systems we’ve built—economics, power, politics, and even art history.

The 2023 work La Comédie Humaine, Farewell pushes that sentiment further. The farewell here is not personal, but societal. It’s a goodbye to illusion—maybe even to hope. The composition carries more weight, more finality. There’s a sense of collapse, not necessarily physical but moral. The references to Dante’s Divine Comedy are apt: Tsalamata isn’t showing us paradise, but purgatory, maybe even hell. These are not abstract ideas. Her commentary lands hard in the present. The visual language is clean but loaded. This isn’t chaos on paper—it’s control. A kind of order that suggests a system too perfect to be fair. Every detail asks you to look again and see the slow erosion of empathy, the bureaucracy of pain, the hollowed-out rituals we call progress.

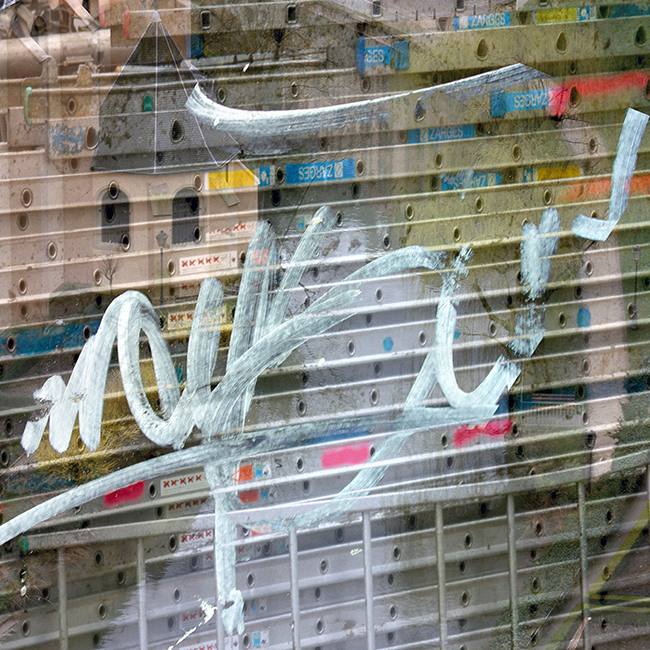

The shift in tone is clear when looking at her Cityscapes: Utopian Cities. While the Comédie Humaine series pulls us into disillusionment, the Utopian Cities try to reimagine space—physically and philosophically. Here, Tsalamata blends urban photography with fragments of her intaglio print work, letting the past and present collide in composite cityscapes. These are not clean visions of the future. They are layered, stitched, and sometimes jagged. Still, there’s something hopeful in them. They feel like an effort to reclaim possibility. The cities she constructs aren’t real, but they’re grounded in real places she’s visited. They hold tension between the ideal and the experienced. By using expanded printmaking techniques, Tsalamata reshapes photography into something tactile and reflective. In these works, architecture becomes metaphor—human design as a framework for how we live together, or don’t.

What ties these series together is the artist’s refusal to gloss over contradiction. Her work is not decorative. It’s interrogative. There’s no comfort in Give Me Your Hand, no resolve in Farewell, and even in Utopian Cities, the optimism is cautious. Tsalamata doesn’t preach, but she observes with clarity, and what she sees isn’t always pretty.

Yet, she’s not cynical. That’s important. Even in her sharpest critique, there’s a sense that looking honestly—at history, at society, at ourselves—is still worth something. Maybe the worth of that act is the only thing we can be sure of. Her use of archival print methods on pure cotton paper is telling. It’s not about luxury; it’s about permanence. She’s making work to last, to be read again when we’ve forgotten what it meant the first time.

In an art world often preoccupied with spectacle, Tsalamata offers substance. Her work is not loud, but it resonates. It doesn’t ask to be liked. It asks to be considered. And in that way, it stays with you—quiet, steady, and a little bit haunting.