Doug Caplan was born in 1965 in Montreal, Quebec. His story with photography starts quietly. In his early teens, he got a black-and-white Polaroid camera—a gift from his parents. It wasn’t much, just a plastic body with a disposable flash and a signature smell from the film chemicals. But it stuck with him. Not as a job, not even as a deep passion at first—just a feeling that photography had something to offer. Years passed. Life happened. It wasn’t until the early ’90s, after getting married, that Caplan picked up a camera again. This time, it stayed with him.

He’s explored both analog and digital photography over the decades, always with a sense of curiosity about what people usually miss. He’s not chasing spectacle. He’s looking for what sits in the corner of your eye—the parts of the world that aren’t supposed to be beautiful but are.

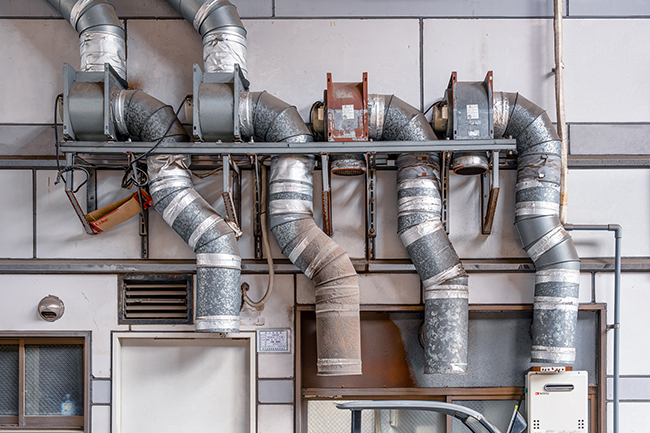

Ductwork Ballet

In Ductwork Ballet, Caplan captures a quiet wall in Tokyo—something most of us would walk past without a second glance. The photo isn’t about a person or an event. It’s about ducts. Pipes. Functional metal tubes crawling across a building like arms mid-dance. Some bend tightly, others stretch long and low. They don’t follow any visual rule. They follow necessity. And yet, when Caplan frames them, something else emerges—rhythm.

He doesn’t force meaning into the image. He lets the structure reveal its own. It’s choreography without intention. A kind of accidental grace. That’s Caplan’s strength: showing you the design hiding inside chaos, the beauty stitched into the things we built just to “make work.” It’s not romanticized. It’s just honest, which somehow makes it more poetic.

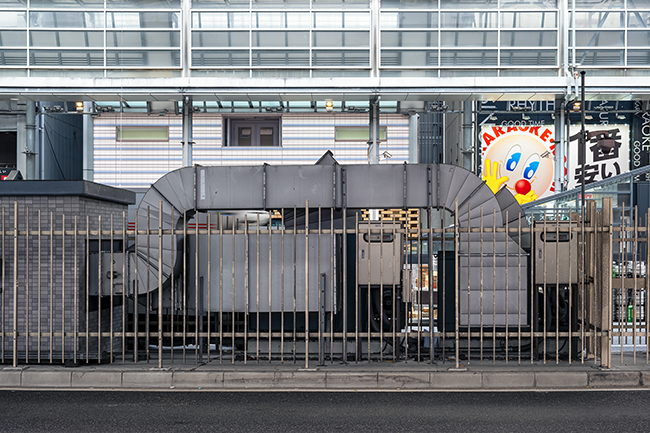

Snakes & Ladders

Another piece, Snakes & Ladders, also in Tokyo, continues the theme of overlooked infrastructure. In this photo, Caplan dives beneath the surface—not literally underground, but below the surface of what we typically look at. Pipes twist like veins. Ladders lean at odd angles. There’s a yellow-lit window glowing in the corner like a quiet heartbeat.

The title plays with the childhood board game, but this isn’t playful in a loud way. It’s subtle. The game here is the one cities play with function and chaos. You think cities are designed. But look closer and you’ll see improvisation. Workarounds. Unspoken decisions. The photograph is calm, almost meditative, but layered with tension. These are the pieces that hold a city together, yet nobody pays attention to them—until Caplan shows you why you should.

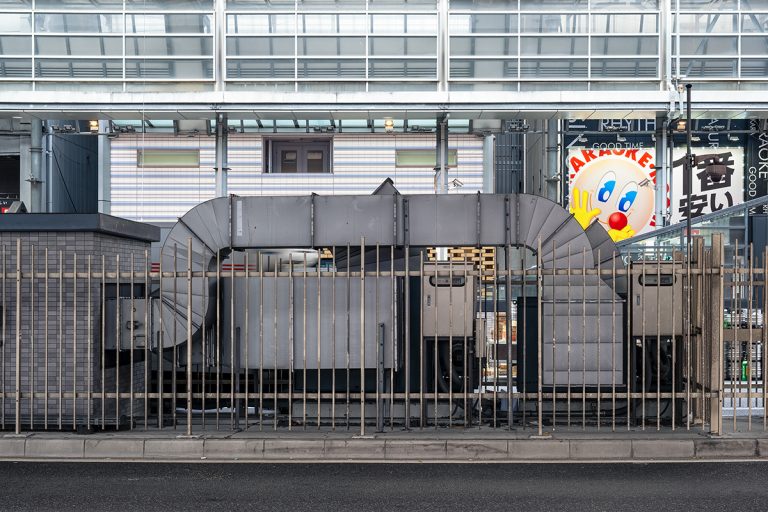

The Absurdity of Existence

Then there’s The Absurdity of Existence, shot in Osaka. This one breaks the quiet. It makes you pause. Everything in the frame is tidy: right angles, gridded surfaces, neutral tones. Then there’s a face. A bold, colorful cartoon face stuck onto a structure with no warning, no purpose, no explanation.

It’s funny. But also unsettling. Caplan doesn’t treat the face as an oddity—he treats it as part of the scene. It’s not an accident. It belongs. The message hits fast and clear: the absurd isn’t breaking the system; it is the system. Urban life isn’t just built on plans—it’s built on interruptions, jokes, things that don’t belong but refuse to leave.

What Caplan gets, and what this photograph says so clearly, is that cities aren’t machines. They’re stories. Sometimes those stories are well-organized, but often they’re just strange. And that’s what makes them real.

Caplan’s work doesn’t shout. It points. It notices. Whether he’s showing a quiet dance of ductwork or a grinning sticker on a concrete wall, he asks you to look again. Not for something grand. Just for what’s there. And maybe that’s the heart of his photography: seeing what’s always been in plain sight—but never quite like this.