John Gardner’s sculptures aren’t about perfection or polish—they’re about presence. Working from his studio in South Africa, Gardner approaches clay and bronze like a conversation. He isn’t trying to copy a face. He’s trying to catch a moment—a pause, a grin, a flicker of thought. His work moves between portraits of well-known public figures and quiet, abstracted forms, but the goal remains steady: to make something that feels lived in. For Gardner, a sculpture is successful when it feels familiar. Not necessarily in its features, but in its energy. Something you don’t just look at—you feel like you know it. You’ve met it before. His pieces hold weight, not just in material, but in memory.

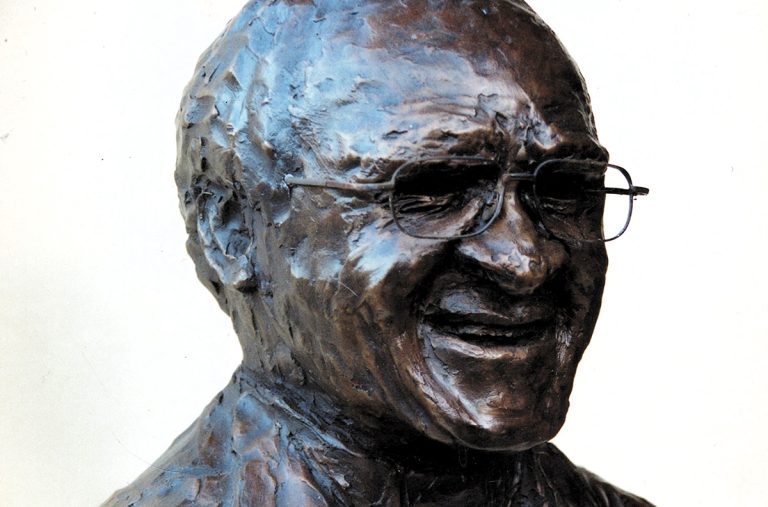

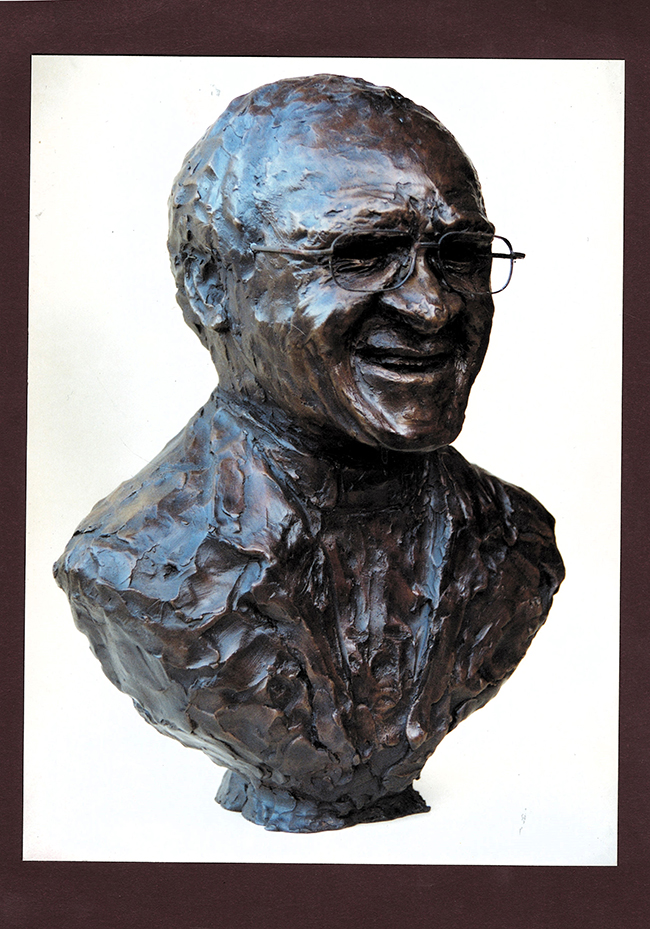

Desmond Tutu: A Likeness Through Laughter

The bronze of Archbishop Desmond Tutu came to life with laughter. It was the first in Gardner’s Legends of Africa series. When Tutu sat for the bust, he immediately pointed to the work in progress and grinned: “I like the nose.” Gardner, half-joking, offered to adjust the lips. Tutu burst out laughing—“If you do that, I’ll look like a real African!” That was the moment Gardner was waiting for. He reached forward, lifted the Archbishop’s cheeks with both hands, and locked that expression into the clay. “Done,” he said. “But you’ve only had five minutes,” Tutu noted. “That’s all I needed,” Gardner replied.

The sculpture captures that spark perfectly. Not just the physical features, but the warmth, playfulness, and presence of a man whose legacy is deeply human. What makes the work especially layered is that Tutu was, at the time, preparing a speech for the funeral of Beyers Naudé—a fellow freedom fighter. The contrast of grief and levity adds texture to the story behind the bronze.

The artist’s proof was auctioned at an Elton John Charity event in 2005, raising money for HIV/AIDS initiatives in Africa. It was a fitting echo of the values both artist and subject shared.

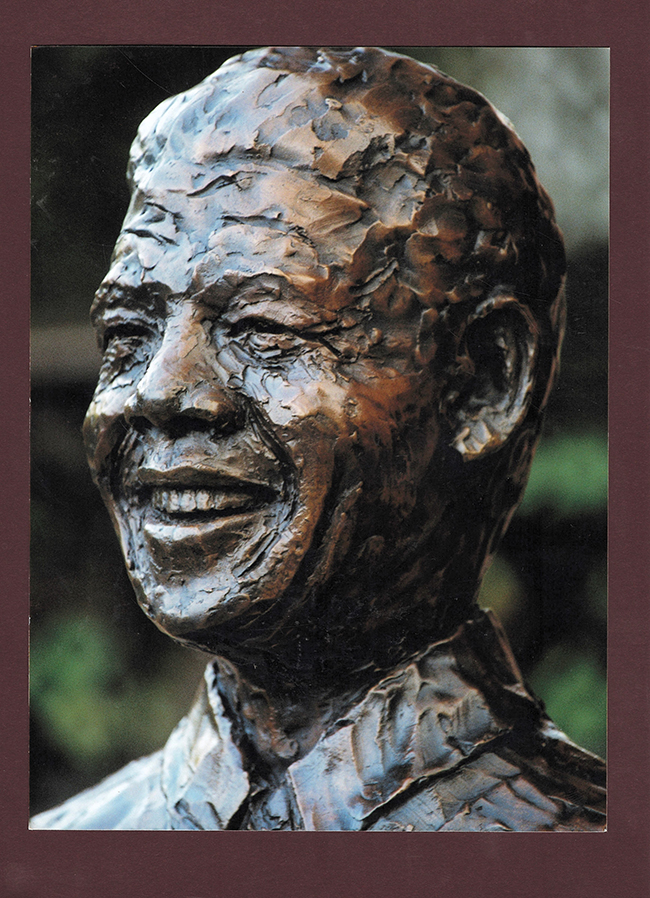

Nelson Mandela: A Wordless Tribute

Gardner’s bust of Nelson Mandela wasn’t born from a dramatic unveiling. It found its meaning in a quiet glance. Mandela kept the artist’s proof on his desk. One day, Verne Harris—his longtime assistant—caught sight of Mandela standing in the doorway, simply smiling at the sculpture. No explanation followed. It didn’t need one.

This piece doesn’t try to enlarge Mandela’s stature. It narrows in on something more personal. The face is soft. The presence is still. Gardner wasn’t reaching for the grandness of Mandela the statesman—he was reaching for the man behind the name.

The edition is limited to ten casts. Each one holds that same calm presence. Something felt rather than announced.

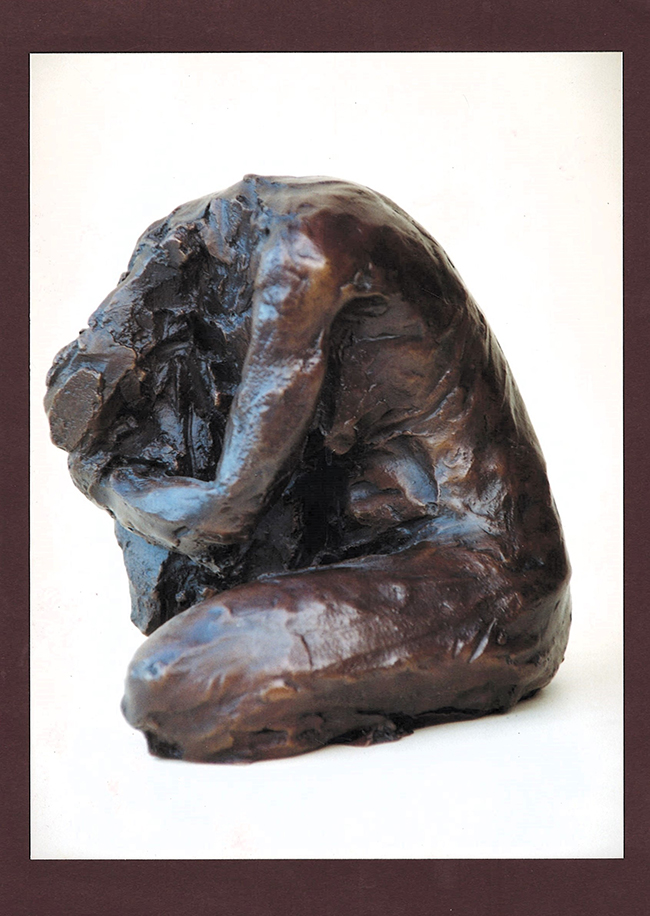

Masculine and Feminine: A Quiet Form

This piece breaks from the portrait work and moves inward. Masculine and Feminine is an abstract, reflective form. There’s no face. No gaze. Just posture—closed, self-contained, almost curled in thought. It could be seen as a body resting, a body shielding, or a body turning inward. It doesn’t ask for interpretation. It simply exists in its shape and quietness.

Gardner uses bronze here like he does in his portraits, letting its natural roughness show. There’s no smoothing down. The marks remain, giving the piece a kind of vulnerability. It’s about the space between strength and softness, the balance we carry within.

What His Work Carries

Gardner sculpts fast. He doesn’t aim for glossy finishes or high detail. Instead, he chases recognition—the feeling that what’s in front of you isn’t just a sculpture, but someone. Something. A story.

His fingerprints are often visible in the final casts. He doesn’t hide the process. He honors it. That honesty runs through all his work, whether it’s a well-known leader or a faceless form. Gardner doesn’t freeze people in bronze to be worshipped. He shapes them to be remembered.

And not just for what they did—but for how they felt to be near.