Helena Kotnik’s work lives at the edge of the visible and the internal. Trained in Barcelona and Vienna—two cities known for their rich artistic lineages—she brings a clear academic foundation to her practice. But what makes her work resonate isn’t just technique. It’s how she uses that training to question, explore, and dissect identity, memory, and the roles we play. With a Bachelor’s in Fine Arts from the University of Barcelona and further studies at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna, plus a Master’s degree, Kotnik stands at the intersection of psychological exploration and vivid, layered aesthetics.

Her paintings aren’t simply portraits or narratives. They function more like mirrors—sometimes fogged, sometimes cracked—where the viewer can catch glimpses of their own thoughts and projections. Kotnik doesn’t hand over all the answers. She offers pieces. Hints. Symbols. She paints the architecture of the inner life, using form and color as her language.

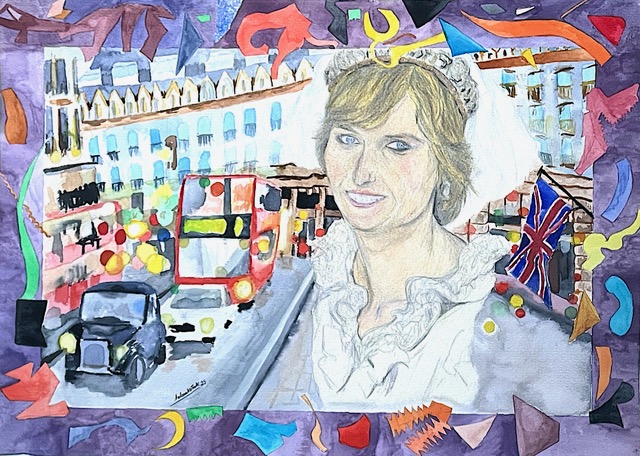

The Princess

70 x 50 cm

Gouache, colored pencil, and watercolor

2025

The Princess is one of those pieces that stops you—not because it shouts, but because it whispers something you half-remember. The title may suggest a fairy tale, but Kotnik’s version is far more layered. There’s no castle, no tiara, no glitter. Instead, what you see is a quiet, almost reflective presence. The figure in the work exists somewhere between memory and myth.

At first glance, you might think of Lady Diana—Princess of Wales—whose life and death still haunt the cultural imagination. Kotnik doesn’t declare that reference outright, but she lets it hover in the air. The suggestion of Lady Di isn’t literal. It’s psychological. It’s about how we create idealized images of women, how those images can trap and define, but also how they can carry dreams, longings, and the need to be seen.

The figure in The Princess seems caught in that space. She’s more than one person at once: an icon, a self-image, a memory. Kotnik paints her not as a subject to be gazed at, but as someone actively holding her own complexity. Through gouache, watercolor, and colored pencil, the layering adds to that feeling. There’s softness, but also sharpness. Color is used deliberately—never decorative, always expressive. Every stroke seems to ask: What does it mean to be visible?

It’s tempting to try and decode her—“Is this Helena herself? Is it a cultural symbol? A composite?”—but Kotnik resists such narrowing. The power of the piece lies in its openness. It becomes a vessel for any viewer to place their own associations and projections. It’s the kind of work that grows the longer you sit with it.

Beyond the figure, there’s atmosphere. The background isn’t blank, but it doesn’t overwhelm. It allows the subject to hold space without distraction. In that silence, we sense something unspoken—an internal monologue, maybe, or a dream that never fully ends. There’s a tension here between the personal and the public. A woman painted as “princess,” but also as a full self, layered with ambiguity and agency.

This is a thread that runs through much of Kotnik’s practice: the reclaiming of feminine identity beyond surface aesthetics. She’s interested in how women are represented, how they represent themselves, and where those stories intersect. The Princess captures that inquiry with clarity and care. It’s quiet, but it asks big questions.

There’s also something deeply human in the work—a universal reach. Anyone who has struggled with the gap between how they’re seen and who they are will recognize something here. The painting isn’t just about one woman. It’s about the broader experience of being read, misread, admired, constrained.

Kotnik’s choice of media—gouache, watercolor, colored pencil—emphasizes that mix of control and looseness. These materials can be precise, but also fluid. They let her build transparency, allowing the viewer to see the work’s construction. That vulnerability—the visibility of process—feels connected to the subject matter. It’s a painting about a woman trying to hold herself together in a world that projects too much onto her. And the work itself does the same. It holds together, layer by layer.

In The Princess, Helena Kotnik shows us what art can do when it steps into the space between identity and myth. It’s a portrait, yes—but not of one person. It’s a portrait of longing, expectation, and the quiet power of self-representation.