Meet Haeley Kyong, a creator who works in quiet defiance of the noise. Born and raised in South Korea, Kyong’s life has been one of cultural crossings and creative contemplation. Her work doesn’t shout—it hums. It doesn’t explain—it invites. With a background shaped by rigorous study at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University and further refined at Columbia University in New York City, she moves easily between structure and intuition. Kyong’s art, often minimalist in appearance, is built on layers of thought, emotion, and restraint.

There’s a calm insistence in her practice—a belief that art can be a vessel for personal truth and universal resonance. She draws from philosophy, geometry, and natural order, connecting deeply with the idea that art can express something essential about existence. Her pieces are less about decoration and more about quiet recognition. Something ancient, something now.

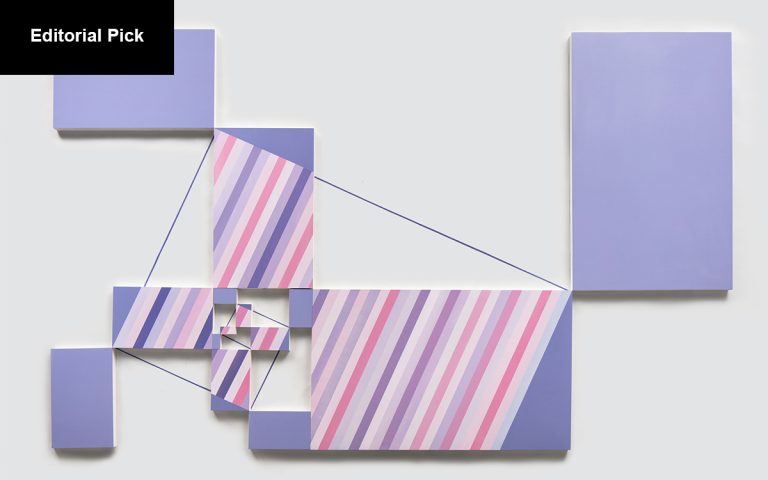

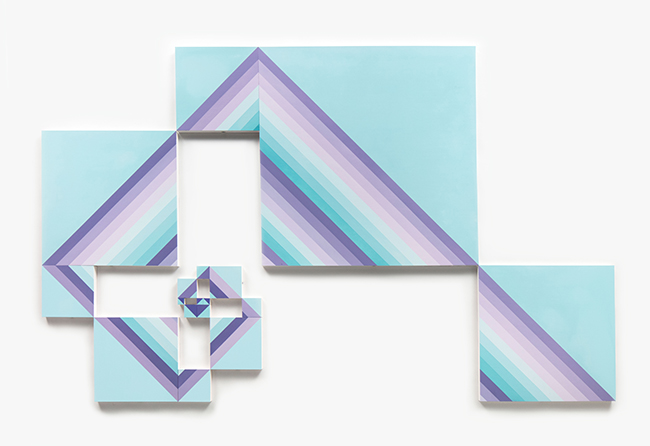

The Nexus: In Sequence I & II

In her paired works The Nexus: In Sequence I and The Nexus: In Sequence II, Kyong engages with the Fibonacci sequence—one of the most quietly pervasive patterns in nature and mathematics. Many artists have drawn on the sequence before, but few with the intention Kyong brings: to explore not just aesthetic harmony, but philosophical duality.

She noticed, while drawing the Fibonacci spiral, that the underlying composition was made up of rectangles and squares—two basic shapes, both representing growth, both expanding according to the same ratio, yet differing in form. For Kyong, this became more than geometry. It became a metaphor for yin and yang.

Her insight is simple, but resonant. Rectangles and squares, like yin and yang, are not in conflict. They don’t cancel each other out. They exist within the same system, bound by rules that allow for infinite variation. They grow, not by overtaking one another, but by building upon each other. The strength of the system lies in their interplay.

Kyong’s approach to rendering these shapes is clean, intentional, and meditative. She doesn’t overload the viewer with detail. Her materials—often pencil, ink, or acrylic on paper—are secondary to the process. The works feel like diagrams of thought, visual mantras. In viewing them, one might feel time slowing down. The pieces breathe.

But this isn’t about math for math’s sake. It’s not technical. Kyong’s choice to explore the Fibonacci sequence through the lens of Eastern philosophy shifts the focus from logic to balance. It’s a return to the essential—to the idea that complexity can arise from simplicity, and harmony from opposites.

The title The Nexus fits. A nexus is a point of connection, a coming together. Here, what’s connected is not just shape to shape, or line to line, but ideas to emotions, culture to nature, self to system. The art is both personal and universal. You don’t need to know the Fibonacci sequence to feel its pulse in the drawings. You don’t need to study Taoism to understand the tension and release between forms. The work stands on its own, like a quiet room that lets you think.

Kyong’s process, from sketching to refinement, is slow and deliberate. She invites the sequence to unfold, rather than forcing it into place. In a world addicted to speed and spectacle, that patience is a kind of resistance. These works are not meant to be glanced at. They ask to be lived with.

Though minimalist, they are not cold. They carry the warmth of reflection. One might imagine Kyong seated in a quiet studio, tracing a spiral, watching it build on itself, letting each corner lead to the next. There’s a sense that the work is a collaboration—with form, with concept, with time.

Her work resists categorization. It’s not easily explained in the language of trends or genres. It comes from a place older than that—a lineage of artists who listen before they speak, who observe before they paint. Kyong’s pieces are grounded, and they give the viewer something to hold onto: a shape, a ratio, a breath.

In The Nexus: In Sequence I & II, Haeley Kyong doesn’t offer answers. She offers a structure. Within that structure, growth happens. Tension exists. Beauty emerges—not from adornment, but from clarity.

And in that space, the viewer is free to wonder.