Caroline Kampfraath is a Dutch artist whose work explores the fragile, gritty, and deeply human spaces where emotion meets matter. She doesn’t simply make art; she constructs meaning out of texture, memory, and confrontation. Known for her 3D installations, Kampfraath doesn’t shy away from using unexpected materials—metal cans, old bottles, and even human body casts—layering them into sculptural forms that explore our relationship with nature, society, and ourselves. Her work is personal, but not insular. It invites the viewer into a shared dialogue. Kampfraath’s art is not about shock value; it’s about digging beneath surfaces—literally and metaphorically. Her practice moves between vulnerability and defiance, always rooted in a quiet insistence on emotional honesty.

Her work balances the symbolic and the physical. Objects are chosen not just for form but for their weight in meaning. Through this, she builds a visual language that speaks of pain, connection, memory, and resistance—especially as it relates to the experience of being a woman.

One such work, Under My Skin, is a piece that leans hard into these ideas. Created for the Women’s Museum in Bonn, Germany (Frauenmuseum Bonn), the sculpture installation is a deeply unsettling and moving response to the continued policing and dehumanization of women—particularly online. The installation takes the form of dresses made from horseskin parchment. At first glance, this choice might seem harsh or unusual. But parchment, traditionally used as one of the oldest mediums of communication, here becomes a metaphor for how the female body has long been treated as a message board—marked, interpreted, judged.

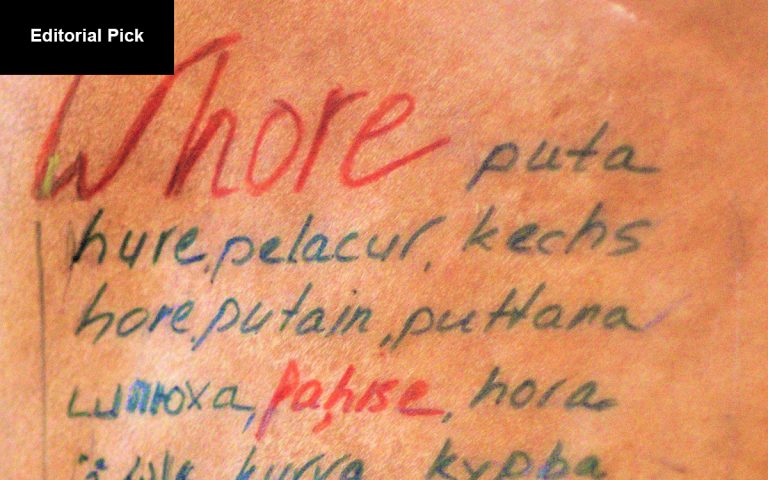

These dresses are not designed to be worn. They resemble skins, removed and preserved. There is a rawness to the work—both in the material itself and in the meaning embedded in it. Each dress bears the marks of tattoo-like inscriptions. Kampfraath is pointing to the language that is too often thrown at women online—derogatory, dehumanizing words that transcend national boundaries. Among them, the word “whore”—a term that appears across languages and platforms with chilling consistency. It’s not just a word; it’s a weapon. And Kampfraath has carved it into her sculpture, refusing to let us look away.

Yet Under My Skin is not just a scream against violence. It is also a call for solidarity. Inside the dresses, Kampfraath includes a quote from Anaïs Nin:

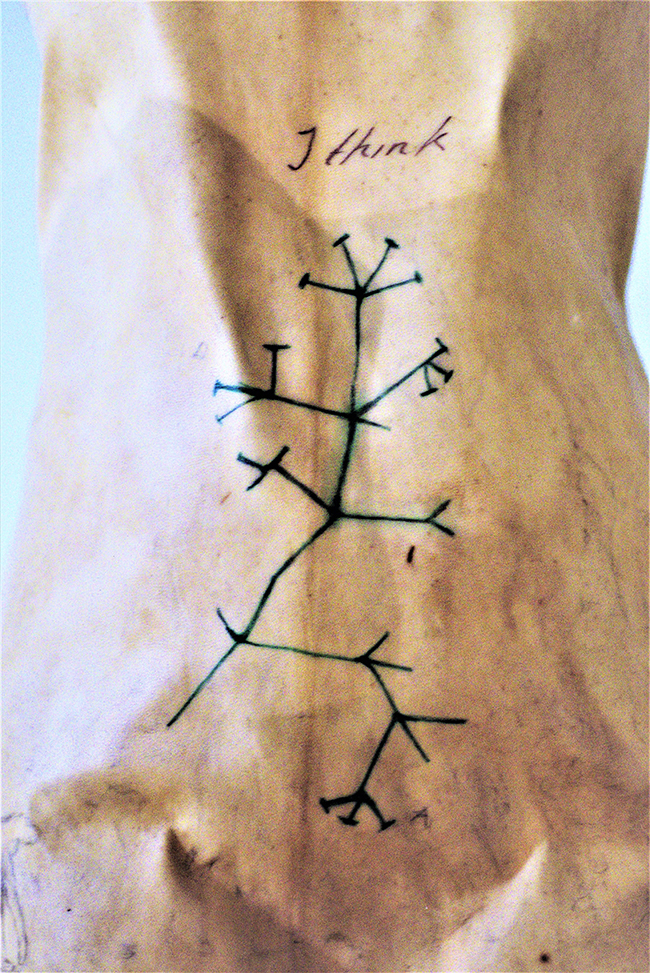

“Each friend represents a world in us, a world possibly not born until they arrive, and it is only by this meeting that a new world is born.”

This is where the work turns. It doesn’t leave the viewer stranded in the violence. It points to care, to connection between women, to the power of female friendships that serve as lifelines in a hostile world. The inclusion of this quote inside the garments—not on the surface—suggests something internal, protective, even sacred. The outside might be scarred, branded, or judged. But the inside holds tenderness, support, and resilience.

The installation is quiet. It doesn’t shout. But it stays with you. The parchment, an ancient material, now holds a contemporary message. The dresses hang like skins, but inside them are worlds, friendships, and new beginnings. Kampfraath isn’t offering easy hope, but she is insisting that we recognize both the damage and the care.

This is what makes her work so layered. It doesn’t operate on a single register. It’s sculpture, yes, but it’s also protest, poetry, and conversation. It demands attention not just to what is visible, but to what is felt. The physical material—the horseskin—is not just a shock tactic. It carries meaning: the idea that women’s bodies are often treated as territory to be written on, policed, and disciplined. But Kampfraath doesn’t stop there. She turns the same material into a vessel for solidarity. What was once parchment for religious texts or legal codes becomes a garment for inner truth, for female kinship.

In Under My Skin, Caroline Kampfraath brings together history, trauma, and care. It is a sculpture, but more than that, it is an offering. It asks us to look beneath appearances, to listen to what lies inside, and to think about how women continue to be shaped—by words, by threat, but also by love and loyalty.

Her work doesn’t resolve anything neatly. That’s not the point. What she does offer is presence. A space to feel, reflect, and maybe recognize something about our own skins—and the stories etched into them.