Haeley Kyong doesn’t make art that asks to be decoded. She makes art that asks to be noticed. A lot of contemporary work is built to be explained—its first move is intellectual. Kyong’s work takes a different route. It arrives through sensation first, then thought follows. You feel something shift—your breathing, your focus, your mood—before you can name what caused it. Her practice rests on a steady belief that art can reach us ahead of language, before we start labeling, organizing, and deciding what we’re supposed to think.

Kyong was raised in South Korea and later spent key years in New York, studying at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University and at Columbia University. That path shows up in the balance of her work. There’s an underlying discipline, but it never feels tight or sealed. There’s control, but also room. Her pieces reflect training and intention, yet they don’t feel like demonstrations. They feel like decisions made for clarity—nothing more, nothing less.

Minimalism is often mistaken for distance, as if fewer elements automatically means less emotion. Kyong challenges that idea. Her work is restrained, but not detached. By removing the unnecessary, she makes the necessary more intense. The pieces don’t get louder in a dramatic way; they get more present. With less to distract you, a color relationship or a small shift in spacing can hit with surprising force.

When you’re in front of her work, you aren’t being pulled into a storyline. You’re being presented with a handful of essentials—shape, color, interval, rhythm. The invitation isn’t to “understand.” It’s to engage. Kyong’s work isn’t a one-way delivery system. It holds its place and gives you space to bring your own attention to it. That exchange—the artwork’s structure meeting your state of mind—is where it comes alive.

Her compositions often revolve around basic forms and carefully calibrated color. What’s striking is how sensitive the work is to minor adjustments: a hue warming slightly, an edge softening, a pause between forms stretching just a bit. These changes can alter the emotional temperature of a piece the way a small key change alters a song. That musical quality is hard to ignore—limited components, precise placement, and an atmosphere that changes depending on what you carry into the room.

Kyong’s intent is to slip past the inner commentator. The work doesn’t rely on art-world references or clever visual riddles. It leans on a more universal mechanism: recognition. A response that happens in the gut, not the glossary. You may not be able to explain why a certain arrangement feels calm, or unsettled, or quietly energizing—but the reaction happens, and it becomes part of what the artwork is doing.

Color Wave is a strong example. At first glance, it reads as a field of tiles, each with its own palette—like a mosaic assembled from many individual choices. The whole holds together, but the real pull is the variety within it. Each tile carries a slightly different mood. Some feel open and bright; others feel muted, inward, held close. And still, they sit side by side without clashing, building a single surface out of difference.

What the piece avoids—smartly—is turning that into a simple statement. It’s not a poster about togetherness. It’s an experience of it. Individuality doesn’t get erased; it gets included. Contrast becomes the binding element rather than the problem. The work naturally brings to mind how different lives and perspectives can exist in proximity—distinct, sometimes contradictory, yet still part of one shared frame.

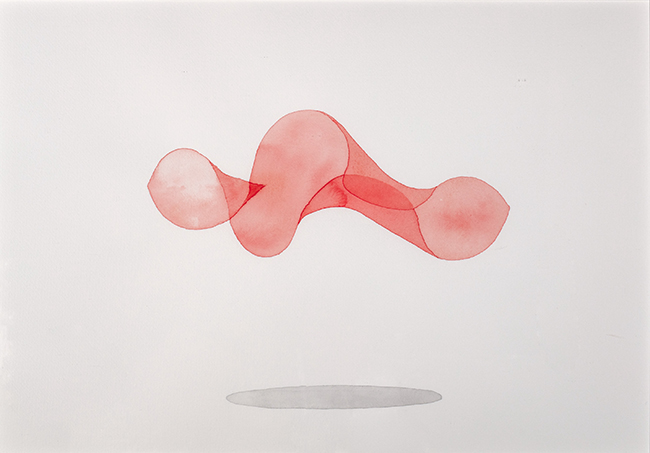

If Color Wave holds many parts in one field, Kyong’s watercolor series Undulation leans into motion—internal motion, the kind that’s hard to pin down but easy to recognize in yourself. The series includes five paintings centered on a simple square that appears to move through space. The form stays basic, but its behavior becomes expressive. It lifts, dips, tilts, and shifts posture like a body does in moments of uncertainty—wanting to move forward, feeling a tug to pull back.

Kyong has tied Undulation to the sensation of a bird in flight, and you can feel that airy lift in the way the form seems to catch space. But the work isn’t literally about birds. It’s about what flight stands in for: freedom, risk, the fragile balance between release and fear. That push-and-pull gives the series its emotional charge. The square becomes a proxy for what many people experience internally—courage and hesitation, momentum and resistance, letting go and holding on.

Across the five paintings, the square passes through different states, almost like a short sequence captured in fragments. Watercolor matters here. It softens edges. It allows pigment to bloom and drift. It resists strict boundaries even when the central form is geometric. The medium adds breath—transparency, bleed, a sense of time passing in the paper itself. You’re watching a simple shape act like a feeling, which is why it stays in your mind after you leave.

What keeps people returning to Kyong’s work isn’t spectacle or complexity. It’s the steadiness of the choices. She doesn’t over-explain because she doesn’t need to. She builds a situation where the viewer can arrive at something personal without being instructed. The work is quiet, but it isn’t passive. It asks for attention, and it gives something back.

Her training supports that restraint. Education can sometimes push artists toward overbuilding—adding more to prove skill, filling every inch to show range. Kyong resists that impulse. She refines rather than decorates. The work feels resolved without feeling overworked. There’s room for thought to move, and room for emotion to rise without being guided by a script.

At the center of her practice is introspection—not as a buzzword, but as a real event: that moment when you notice your own response in real time. Kyong’s work can function like a pause in a crowded day. It slows the internal noise just enough for something honest to show itself.

And maybe that’s the quiet proposal her work makes: we don’t always need more. Sometimes less is what lets us feel what’s already there.

Haeley Kyong’s art is pared back and deeply resonant. With a small toolkit—shape, color, rhythm—she opens a wide emotional range. The work doesn’t demand attention. It holds it. And in that steady focus, it offers something rare: a clear space where a viewer can reflect, reset, and recognize themselves.