Vicky Tsalamata works out of Athens, Greece, with a practice that keeps one foot in history and the other in the present day. Her prints echo the scope of Honoré de Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine—not as homage, but as a framework for looking at what people do to each other, what systems reward, and what gets lost along the way. There’s humor in her approach, but it isn’t comforting. It’s sharp, sometimes sarcastic, and aimed at the gaps between what we say we value and how we actually live.

Her imagery pulls from moral storytelling traditions—Balzac’s social panorama, Dante’s vision of judgment—and filters them through the tempo of contemporary life: accelerated routines, widening inequality, and a strange loneliness that can exist even in constant connection. Tsalamata’s work asks the viewer to pause and take stock. Not in a sentimental way, but in a clear-eyed one: what does it mean to be “important” inside a machine that rarely treats people as such?

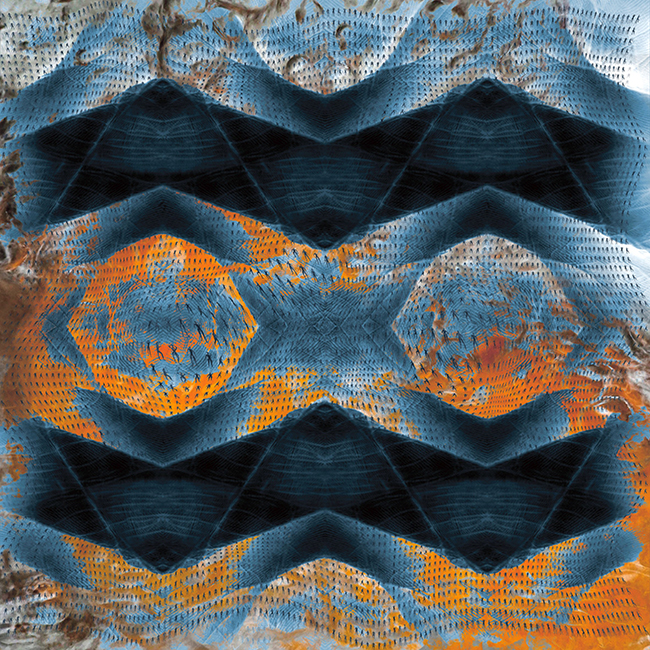

“La Comédie Humaine”

Tsalamata’s graphic work La Comédie Humaine begins with a literary title, but it quickly becomes something broader: a visual map of how modern life behaves. The reference to Balzac signals scale—society as a sprawling cast of roles, motives, and compromises—while the nod to Dante’s Divine Comedy brings in another layer: the question of judgment. Dante’s poem imagines a universe where actions carry weight and consequence. Tsalamata’s version is less certain that justice arrives on schedule. Instead, she uses irony to show what happens when morality is bent by power, and when people adjust to that bending as if it were normal.

At the heart of the work is a blunt observation: in the “grand scheme,” individuals can feel small—replaceable, pushed around by forces that don’t ask permission. Tsalamata leans into this discomfort. Her commentary moves across time—past and present—suggesting that the pattern repeats, just with different costumes. Social norms shift, economies rise and collapse, technology changes the texture of daily life, yet familiar dynamics remain: the weak are pressured, the corrupt are protected, and the machinery of public life often rewards the least generous instincts.

But the work doesn’t settle for cynicism. Tsalamata also frames this condition as a crisis of connection. The irony is that communication has never been easier, yet genuine contact can feel rarer. In her statement, she points directly to what’s missing: love and friendship as essential forces, not decorative ideals. That emphasis matters. It turns the piece from a diagnosis into a demand. If the world is a constant churn—socially, economically, morally—then the human response can’t be passive acceptance. It has to be deliberate relationship: listening, caring, staying in contact even when the larger system trains people to self-protect and detach.

Technically, La Comédie Humaine is built through intaglio and mixed media using seventeen iron matrices worked with intaglio processes. That detail tells you a lot about the way Tsalamata thinks. Seventeen matrices isn’t a shortcut; it’s a construction project. It suggests layering, accumulation, and a commitment to building complexity rather than implying it. Iron, too, carries its own tone: industrial, durable, a little severe. In the context of her themes—social pressure, institutional hardness—it’s a material that makes sense. It supports the idea that the “map” she’s making isn’t airy or abstract. It’s a map made from weight.

Her related work, La Comédie Humaine B’, was selected and is currently displayed in the Main Exhibition of the Guanlan International Print Biennial Nomination Exhibition 2025 at the Guanlan Printmaking Museum, running from December 20, 2025 through April 2026. That placement situates Tsalamata’s work inside a global conversation about contemporary printmaking—where technique isn’t separate from meaning, but tied to it. A print can be intimate, but it can also be architectural in thinking, and her process fits that larger scale.

“Impulse”

If La Comédie Humaine reads like a social atlas, Impulse moves like a clock with its hands spinning too fast. Created in 2025 as an edition of 45 for Patanegra (Pantanegra) Editions in Spain (52 x 38 cm), the work focuses on time—not as philosophy in the abstract, but as something bodily and urgent. Tsalamata describes it as the eternal flow of time in relation to the “kinetic momentum” of human life: the push that keeps people moving, even when they don’t fully understand what they’re chasing.

Here her sarcasm shifts into something quieter but still pointed. She looks at modern rhythm—deadlines, speed, constant stimulation—and notes how easily people become spectators to their own lives. Real life runs alongside them, and they wave at it from the sidewalk. The work links to Heraclitus’ idea that everything flows, which is less a poetic line than a warning: you don’t get to pause the river. You can only decide how consciously you move within it.

Impulse also connects to Tsalamata’s larger project Awareness, an installation presented at the Krakow International Triennial in 2024, and it continues forward into an international collaboration: the XII Graphic Arts Folder project for 2026, bringing together invited American and European printmakers. In that context, Impulse becomes both personal and shared—a statement about time that’s made through a medium built on repetition, pressure, and transfer. Which is fitting. Because time, too, leaves an imprint—whether we’re paying attention or not.

Tsalamata’s work doesn’t try to flatter the viewer. It holds up a mirror and keeps it steady—showing systems that grind, days that speed up, and the ways people drift from each other inside all that motion. And then it quietly insists on what still matters: attention, communication, love, friendship—the human-scale choices that push back against the machine.