Camille Ross was born in 1964 in San Francisco, California. Her childhood was split between radical Berkeley in the 1970s and the quiet rural stretches of Mississippi. That divide—between protest and tradition, urban and rural—never left her. Camille is biracial and part Cherokee, and this layered identity shows up in her work in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. She became a civil liberties activist and documentary photographer, but she doesn’t just document. She observes deeply. Her camera doesn’t simply record what’s there—it often reveals what’s hidden.

Now known for work that highlights marginalized lives and human vulnerability, Camille’s practice has spanned analog film, digital formats, and, more recently, AI. She holds an MFA from the Cranbrook Academy of Art. One period that stands out in her journey is her early 1990s stay in Paris—where two people, a best friend and a lover, helped shape one of the most intimate series of her career.

Paris, 1993: Love, Light, and Film

When Camille Ross moved to Paris in 1992, she wasn’t just relocating—she was entering a period of artistic expansion. She launched the Paris Photography Workshops. But her version of education was grounded in experience. Instead of sticking to a classroom, Camille regularly took her students to the photography archives at the Bibliothèque Nationale. It was there she befriended Claude LeMagny, a well-known curator who would open countless doors for her.

Claude allowed Camille and her students access to the portfolios of both historical and contemporary European photographers. For someone with Camille’s hunger for learning and teaching, it was a dream come true. It’s easy to imagine her poring over vintage prints, sharing insights with her students, and then rushing back to her giant Paris loft to experiment in the darkroom.

That loft wasn’t just a workspace. It was also home. Camille shared it—and the darkroom—with her partner at the time, and together they developed a full curriculum, blending technical instruction with artistic exploration. Among their students? There was Taru.

Taru was Camille’s best friend in Paris. More than a friend—she was a muse. Camille photographed her constantly. The resulting work, Taru, Paris, 1993, isn’t just a portrait. It’s an ongoing conversation in light and shadow. Intimate. Observant. Loyal. Taru later became one of the most respected photography critics in the art world, and she and Camille remain close. Camille has invited Taru as a visiting artist to nearly every university where she’s taught, and there’s an unmistakable tenderness in the way she describes her. You can feel it in the images.

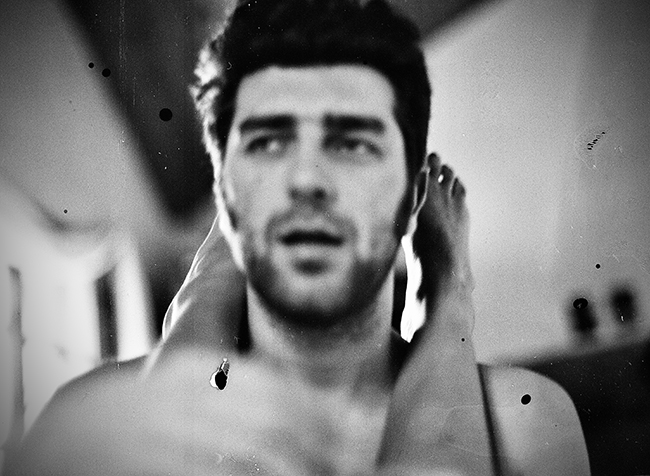

And then there was her boyfriend.

In Boyfriend, Paris, 1993, Camille turned her lens on her partner of that year. These aren’t glossy, stylized portraits. They’re romantic and a little raw. Honest, but with a softness that only someone deeply in love could manage. The connection is clear in every frame—these aren’t just photos; they’re personal documents, love letters in visual form.

These Paris works were shot on film, of course. Camille’s early career was steeped in analog processes. She specialized in nude photography and taught it later at the Academy of Art College and the University of New Mexico, where she chaired the Taos branch. Her film work has a physical, tactile quality—there’s a warmth to the grain, and you get the sense that each frame was developed with intention.

This body of work—Taru, Boyfriend, and other images from that Paris chapter—is being collected in a new retrospective book to be published by Afterhours Books. The volume will include her early film photography, her digital work, and her recent exploration into AI art.

The Zebra Tribe: A Shift into Myth

Years later, Camille created The Zebra Tribe series—an imaginative leap that still holds the same sense of emotional truth. It imagines a sacred tribe, somewhere in the world, that worships zebras. In this fictional mythology, the zebra is a shamanic teacher, a healer. The tribe is made up of all kinds of people—different races, cultures, and appearances—but united by their devotion.

In many ways, The Zebra Tribe is an extension of Camille’s lifelong themes: identity, belonging, the search for healing. But unlike the autobiographical feel of her Paris work, this series embraces myth and play.

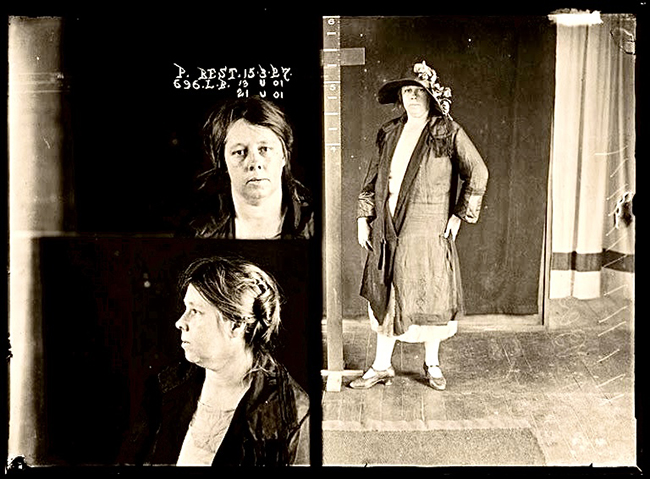

Lady Criminals: A Critique by Camille Ross

Lady Criminals by Camille Ross is a New Media project that examines how women in the penal system are often punished for surviving trauma rather than receiving care. Through archival mugshots and research, Ross explores the stories of incarcerated women—many of whom are survivors of childhood sexual abuse, domestic violence, and mental illness. These women are criminalized for actions often tied directly to their abuse, especially in cases of self-defense.

The project highlights Aileen Wuornos and Sally McNeil, both of whom were failed by law enforcement and sentenced harshly despite histories of extreme violence inflicted upon them. Ross also reflects on the historical criminalization of gender nonconforming individuals and how photography was once used to pathologize women’s bodies.

This series is a visual and critical reckoning with how society continues to blame and punish women for their own victimization, rather than offering treatment, protection, or justice.

Still, whether photographing a best friend in a loft or imagining a tribe dancing in zebra masks, Camille Ross never strays far from her central questions. Who are we? What do we see in one another? And what does love—whether it’s friendship, romance, or shared belief—look like when no one is posing for the camera?

Her work doesn’t give easy answers. It offers something better: a chance to look again.